New Work New Culture Reader

Prototype Edition

Table of Contents7 Preface

By Frank Joyce

9 Introduction: A Conversation about new work new culture What’s Wrong with “Old” Work? 19 The JOB System

20 Is Progress Good for Humanity?

By Jeremy Caradonna, The Atlantic

24 Four Calamities Destroying America’s Economy Being Ignored by Elites By Frithjof Bergmann, AlterNet

27 How Community Production Can Reduce the Cost of “Life Necessities” by Frithjof Bergmann

29 A Critique of Mass Manufacturing

by Frithjof Bergmann

32 Looking Deeper. Thinking Bigger.

by Frank Joyce, AlterNet

35 Is it Possible to Build An Economy Without Jobs?

by Frank Joyce, AlterNet

42 In the Name of Love

by Miya Tokumitsu

What is New Work?

48 After the Jobs Disappear

by Juliette Schor, NY Times

50 Detroit: BuildingCommunity and the New American Revolution by Peggy Kwisuk Hong

Food

57 How to Turn a Vacant Building into an Urban Farm

By Bryan Smith, Chicago Magazine

58 Feedom Freedom Blog, “Grow a garden, grow a community.” by Wayne and Myrtle Curtis

Finance

Manufacturing

63 Re-imagining Work: Another Production is Possible

by Rick Feldman

65 Brightmoor Youth Entrepreneurship Project, excerpt, SBS broadcasting

67 Model D, On the Ground: Youth Entrepreneurship in action by Matthew Lewis

69 New Work and Community Production: The Eyes of the World are on Detroit, by Barbara Stachowski

71 A Brave New ‘Work’ World

by Larry Gabriel, Metro Times

74 Create Anything Anywhere

by Blair Evans

75 Green City Diaries: Fab Lab and the Language of Nature

Model D and the Green Garage Urban Sustainability Library

Services

Energy

82 Community Electricity Lights up Spain

by Inés Benitez, IPS News

Art & Entertainment

87 Old World Meets New

by Linda M. Erbele

New Culture

The Environment

97 self evident truths in environmental justice

Emmanuel Pratt,

Governance

101 Detroit’s Grassroots Economies

by Jenny Lee and Paul Abowd

105 Cities In Revolt: Detroit

by Shea Howell

109 Beloved Community,

by Tawana Petty

110 New Work Field Street Collective’s New Paradigm

by Larry Gabriel, Metro Times

Education

115 New Work/New Culture education (From the ‘Inside-Out’)

by Bart Eddy

Conflict Resolution

120 Peace Zones for Life, Detroit Coalition Against Police Brutality

Ron Scott and Sandra Hines

123 Restoring the Neighbor Back to the ‘Hood’ Pledge

by Yusef Shakur

Art

126 Garage Cultural is expanding consciousness and horizons for kids in Southwest Detroit by Mike Ross, Metro Times

129 Heidelberg History, Heidelberg Project

www.heidelberg.org

Preface to the NWNC Reader, Prototype Edition

By Frank Joyce

What makes a society prosperous? Is the society/system in which some people have a lot of stuff automatically the best? Is poverty for billions a necessary and permanent condition of human life on earth? New Work New Culture challenges these assumptions.

Actually, New Work New Culture challenges everything. In offering a different way to organize work it opens the door to new thinking about education, government, art and entertainment and our relationship with nature. It seeks to reframe the conversation to reflect the growing inability of late stage race-based capitalism to meet the needs of people or the planet.

At this stage of its evolution, New Work New Culture does not pretend to have all the answers. Or even all the questions. That is why there are sections in this prototype New Work New Culture Reader that have no entries. Yet.

This book is a work in progress and probably always will be. We reject doctrine. We welcome in novation and creative thinking. We are committed to creating and sustaining a dialogue of theory and practice as we find our way.

We join the search for better ways of working and better ways of being because we believe that humans are learning that work impacts culture and culture impacts work. The dominant way of organizing how we work now serves to produce, reinforce and reproduce destructive ways of be ing with one another and with other species.

A few hundred years of thinking and being as required by the slave trade, industrialization, fac tory farming and endless war have taken a worldwide toll. Our collective mental health and our humanity is damaged and compromised.

That said, humans do not emerge from this era empty. We are full of hope, plans and ideas. You will see that in this book.

We invite you not just to read this prototype edition of the New Work New Culture Reader. Please help us in writing many new chapters for the next edition.

We express our gratitude to all of our contributors and especially to Mary Anne Barnett and Rick Feldman for their work in pulling this material together and to Roger Robinson and Ulysses Newkirk for their guidance and support in printing this prototype edition.

7

8

Introduction:

A conversation about New Work New Culture Grace Boggs, Frithjof Bergman, Kim Sherobbi, Barbara Stachowski, Rick Feldman and Frank Joyce.

In contemplating this book we held a conversation in early 2014 to think collectively about some of what we wanted it to cover. What transpired was a far ranging discussion that wound up focusing on the relationship between New Work and New Culture. Participants included Grace Boggs, Frithjof Bergman, Kim Sherobbi, Barbara Stachowski, Rick Feldman and Frank Joyce. Following is a lightly edited transcript:

Frank: Well we wanted to have a conversation that involved you and Frithjof especially to think about the introduction to the book and how we would frame what it is we’re trying to say. So my thought about a question to get us started is “What time is it on the clock of New Work?” Where does New Work fit in where we are now?

Grace: I think we’re at a watershed of civilization. I’ve been reading about the Neolithic period when people started farming and moved from hunting and gathering and began to live on the land. And I think that introduced a partnership relationship between men and women that most people don’t know about. Riane Eisler wrote about it in her book The Chalice and the Blade, and I think to introduce that concept of how living on the land creates a possibility of partnership relationships between men and women and that every transition to a new society as Sylvia Federici points out in her book Caliban and the Witch, offers that possibility. The witch hunts were an attempt to drive women from the land and men also into the cities to become proletarians. And I think to bring that into this New Work thing would be very important.

Frank: Frithjof do you want to respond to the same question or ask a new one?

Frithjof: I would like to respond to the same question. I very much agree with, underscore what Grace just said.

Grace: Well I think the idea new culture has to include a partnership relationship with men and women, and how living on the land restores that possibility.

Frithjof: Well very much so.

Grace: Because women’s ways of caring and thinking become so very important. Do you know the book by Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade?

Frithjof: Yes, I do, I do I do I do. And Grace, forgive me, this is meant to be slightly humorous but I always like to emphasize I was a farmer three times in my life. So I have some idea what living on the land and actually making your living from the land is all about. Quite frankly because I’ve done it.

Frank: Would either of you want to say more about the idea of living on the land and relationships between men and women and the idea of community production?

Grace: I think the ecofeminist movement particularly has pointed out how women’s ways of 9

caring do not count the hours. They’re not like jobs, because there’s something emotionally satisfying about caring, about women’s work. And I think to bring in that aspect of women’s work, and how new work makes that possible would be very important.

Frank: I find that very helpful, because one of my things is to contrast the J-O-B system with New Work. In that context the J-O-B system is all about counting the hours and it’s all about keeping track and it’s all about fighting over the hours and who’s in charge of the counting and what is each hour worth.

Grace: Yes and the Job system is so dehumanizing that people compensate for it through higher wages and through greater production and that jeopardizes the earth.

Barb: You know when women do work, and some men too, you do what has to be done. You don’t check in, you don’t check out; you don’t clock in, you don’t clock out so I think that a difference in New Work and sort of the similarities between New Work and women’s work is that you do what has to be done. There’s no division of what kind of work– all the work is sort of what needs to be done.

Frank: Well an extension of that, of course or maybe it’s just a different way of saying the same thing, is that the J-O-B system controls how we spend our time, within a day and within a week and within a lifetime. The job of being a parent for example within the J-O-B system is to get the kid ready to get a J-O-B. So it controls how we think about parenting and how we thing about education and what it is children need to know. And then of course the children grow up thinking that the purpose of life is to have a J-O-B or to have a career, which is kind of the same thing.

Frithjof: This is not the same thing but it relates to what we’re talking about. I would like to emphasize in whatever we pull from here on in that community production is very like farming only on a different technological level. The overlap and the similarities between the life and the work of farming and the life and the work of community production, obviously but I think that can be pointed out and in some sense I always use the metaphor of a spiral. We are in some sense returning to what farming was like but on a higher level, on higher technological level.

Rick: I want to share a sense of what we’ve learned from other epochs: 1) It was not inevitable that capitalism emerged. People made choices, people lost battles; it was about power and that we’re at a similar moment where ideas matter and technology has provided us with the basis to both take the best from that epoch before capitalism did what it did, but also the best that capitalism did in terms of technology and production, whether it would have happened another way or not we don’t know, but technology provides the spaces for community production. So there’s a new synthesis between technology that emerged, or begins to emerge, I guess it’s always been there, but has clearly emerged an ability to decentralize but also in a global understanding. Because I think what we ought to show is that people can have a quality of life and we can create a quality of life that’s both local that’s also internationally understood and in relationship. We’re not talking about going backwards, we’re talking about going forward but taking those things that were destroyed for the last 4 or 5 hundred years and bring them forth: the women’s way of knowing, the relationship to the land and so

forth, so I appreciate what you’re all saying.

Frithjof: I understand very well what you Richard are saying. I’m asking but at the same time proposing that the make up for a spiral is useful. 10

Grace: Well I think the Agrarian phase of society was almost like a fall of community production. Because we think of the Agrarian mainly in terms of slavery because that was the way this country developed but when you live on the land, whole families live on the land; it’s a very different culture.

Frank: Well I have a question about that. If we go back to small family farms whether in England or Europe or the United States, two things occur to me. One is people made what they needed so if they needed a plow for example they figured out how to make a plow. They operated in communities, so if they needed to build a schoolhouse we all can think back to pictures of a barn raising for example. Mostly families gathered to do something that the community needed. It was small and it was local. Now I think we see as a result of fabrication technology and so on the chance to do that again in a localized comparable way. My question though is a question about technology. Fabrication is a high tech invention/evolution from manufacturing from computers from digital technology etc. etc. So fine, let’s say I can make a television set in a garage. But what if I need copper to make that television set and to run that fabricator but we have exhausted the world’s supply of copper? Then what happens?

Frithjof: That is your question? Can I say something before I answer your question? Namely, I would emphasize both. It’s a duality if you want. It’s dialectical in the sense that there are definitely are similarities to farming and of course we want to recover what has been buried

about farming and that is what we’re talking about. At the same time I would want to insist that there are differences. It’s not simply going back to farming. I think that would be a disastrous mistake to attempt that. So technology does make a very big influence and yes a quick way to put it is we don’t just make our own bread and our own salami and our own butter and our own eggs but to pick up on what Frank just said we are not that far from making our own television sets. We are very close to making our own electricity. I feel that has a sort of symbolic value that is high tech farming so to say. And I would not identify that only with fabricators; I think that’s a big mistake. In what I’m writing I’m trying to break down community production into 10 items or 10 categories. There are 10 things that meaningfully can be done with the existence of technology and each one of those 10 things can make us less dependent on money and less dependence on jobs. Now back to what Frank was saying. For quite some time frankly, I have been saying that no we will not run out of electricity, that’s ridiculous. In fact we are constantly inventing new ways of making electricity and there are now so many ways of making electricity that electricity, the scarcity of it, is almost no longer a problem. And I would say something like that about copper – that if we do run out of copper we’re very smart. We’ll find some other material that will do very well what copper did not as well. So we’ll improve the outcome.

Grace: I think it’s really important when we talk about additive manufacturing to realize that at one point we move from the Bronze Age, which was very rigid, to the Iron Age which was much more pliable so the additive manufacturing does not always have the same materials as previous, you can move, the materials used in the future will probably be not the same as, they will become paper but they will be different.

Frithjof: That’s part of what I’m saying.

Rich: I want to go back to Kim’s question. First, it is critical and that we’re doing the New Work reader in Detroit even though it’s a global conversation taking place. That has to do with the significance of community production in a city that has 50% unemployment among youth, and

11

that is a predominantly black city that emerges from the history of racism and capitalism. We believe through example and through theory that a new meaning of life can be given to that underclass, that outsider class that has historically evolved because of capitalist evolution over the last period. To struggle around community production is to negate seeing people as either parasites or predators but as contributing to humanity and to their community.

Grace: I think that what we need to show actually how the production takes place. To give some sense of you know, the same way in capital, you have the materials and you have the constant capital and the variable capital and we see changes taking place in the materials and all that. I think the introduction needs to give a sense what additive manufacturing really is like.

Kim: I can’t help but speak to the culture and Frank’s question about running out of copper or we run out of materials that were used previously. I understand that it’s definitely a possibility and it may happen that we’ll be using differently materials. But in the meantime as we’re looking for best practices and things of that nature we still have our past. And one of the things that’s happening right now in our present is we’re destroying the earth. So yesterday I was at an event at EMEAC and some people from Africa came. They’re doing a tour around the country and they’re saying “We’re being killed! And this has been happening for over 50 years and nobody said anything and its coming to a city near you! Our women are losing their babies. The oil has killed our crops. We are now starving.” And some of the spillage and some of the garbage and the toxins are now traveling across the world. We have to deal with that right now. So I’m saying that speaks to a culture. If we don’t get this culture together we’re not going to be here to do any of it. We’re not. The earth is going to be gone and we’ve got to look at how we’re treating people, how we’re interacting with each other. None of this will mean anything shortly. It will mean nothing. I mean we want to produce but if we don’t really look at the culture it’s going to even be hard to do anything with fabricators, with farming, with even doing things manually.

Rich: When you say culture what do you mean?

Kim: What I mean is how do we treat each other in terms of are we looking out for our brothers and sister, whether its locally, nationally or internationally. Are we really thinking about them? How do we shift to a more sharing type situation? How do we put in place systems and structures like mediation. We’ve been talking about that with the Peace Zones and what have you. But how do we put those things in place? How do we get our young people to focus in on values of compassion and being trustworthy and responsible and accountable? Not just our young people but all of us, but I think right now that’s one of the things that we should be doing is really focusing on our young people because we’ve missed the boat. To help them, to have compassion for other people. So I’m saying that we, there needs to be a strong emphasis on the more human things that Grace talk about.

Grace: I think the introduction has to have some real anthropology in it and to give some sense of how society has developed; how materials have happened.

Barbara: I’ve really been thinking a lot that the conference might be called New Culture New Work. I’m really feeling the whole women’s way of knowing and community and what I’ve just started thinking in the last couple days that we’ve talked about community production and I’m sure that a lot of people fabricators or 3D printers or a way of making a product or something

12

but it’s also community production, what comes first the chicken or the egg? Is what we need to produce, community? I think Kim and I are kind of on the same place. We need to develop a culture, a mindset; working on community production in the production sense will produce community maybe by proximity. I always go back to the Hmong. I spent the last five days at a

Hmong funeral and as soon as you walk into a space where there are a couple of Hmong people you enter in, it’s almost like I can let out a breath of air because I know somebody has my back. I don’t care what it is. People are paying attention to each other. You can’t even reach for a glass of water. I think part of community production is creating a culture of community. And I really think the women’s way of knowing as the Caliban and the Witch.

Grace: You know I almost feel this introduction is going to have to be like Capital. Rich: Three volumes? Do we get three volumes Grace?

Grace: Go from manufacturing to industrial production to New Work and to trace the development of work. Not only the variable capital but the constant capital of the materials, all that will have to be in there. It will be a quite a work of art.

Frank: By definition then it will be a work in progress. But I’m not just agreeing with you, I think that we do have to capture the long view for one thing. Because let me say a word about old culture, or the current culture and how oppressive it is and let me try to frame this as a question. In a way it’s almost a miracle that any kind of consciousness about New Work, New Culture, women’s way of knowing is entering the public conversation and the movie and your book that preceded it – it is hard to exaggerate how encouraging that is because of how stifling and oppressive and encompassing the culture of the J-O-B system is. What see on television, what we’re given is one false revolution after another. For example social media is revolutionary. No it’s not. We can all think of a lot of examples like that. But I also think we are at a point where there’s a disconnect between growing disenchantment with the J-O-B system and yet people not knowing how to connect to or make something better. Does anybody want to talk about that?

Kim: So the question is what is better? So now I’m thinking about what is better? We’ve been fed that better or good is having a lot of material things.

Frank: Yes, part of the J-O-B system, is that what is better is more. It’s entirely quantitative.

Kim: I wouldn’t even call it the J-O-B system as much as I would say you know, what America has framed and the American dream has been framed to be. The reason that people are in the J-O-B system is because they’re trying to get a certain lifestyle. We’ve all been brainwashed or fed this certain way of being. I’ve been challenging myself and others to think about what is better? In my community is better for us having more things? What has been better for us is having our children safe, having community. So many in my community, in the African American community have said, we didn’t even know we were poor. And now I ask the question, when did you find out? When did you decide you were poor? Who told you you were poor? And you know most of them said “when I went to college.” A lot of people come back and say, “When I went to college and I…” or “When I was exposed to this” because they didn’t have the things and that’s when they felt poor. Prior to that when they didn’t have money, when we didn’t have money none of us felt poor because we had a richer life. So I’m challenging and saying ok well let’s go back, let’s just think about what is better. Is it because of these material things, and I think we got to re-frame that. 13

Grace: I can remember when before people thought things mattered — what mattered was community. What mattered was not being an individual on your own. Rich: But people didn’t know, and this is a question, and I can imagine Jimmy having this conversation about when people, even when I was a kid, you went to the store on a regular basis. So you saw your neighbors. Then people got the larger supermarket and that even started with refrigeration. So when we look at this we have to be very historical to know that people did not know that they were going to consciously give up all those relationships as they became more and more independent. So I didn’t need my in-laws to babysit, I could pay a babysitter, right? I didn’t need to live near my family because I could drive to my family. And if you don’t do it historically it becomes nostalgia for the way life once was. And so the black community did what the American community did which was putting economic advancement, individual freedom above those relationships. And so we’re dealing with this thing now about freedom and choice that we have a necessity that it’s both out of necessity and choice we can create a new way of life. We’re not saying that people should be you know just scratching their fingernails to grow an apple and share an apple. We’re not saying that’s the way, but there is this whole thing between needs and wants and what are the cultural values that are more important. So Jimmy said that in the next American Revolution we will be giving up things, right? That’s a whole concept versus to get our humanity we have to give up things, right? That way people in Ghana or Bangladesh don’t have to be the garbage dump for our way of life.

Kim: So I’m glad you said it because I’ve been saying we have to go through it to understand it. Now that we know what comes out of being materialistic, let’s look at the best practices in our community, and lets create something else. So that’s the way I’ve been framing it to people. Now that we know we have to go through what we didn’t know, but now we know. I’ve also been saying as we talk to our children who are very angry, who are saying you all have not taken care of us. You’ve left us out here and we’re angry at you. So our conversation with them is we didn’t know. We thought too that it was going to be ok, but we can start from here. That’s where we should be in our conversation with our children also.

Frithjof: Can I say a couple of things? One thing is that on the issue of creating community I would want to emphasize that working together, that community production, that making things in the community, a community making things, is a way of creating community. And maybe it’s one of the most effective and powerful and feasible ways of creating community. I think working together does create community maybe more than all kinds of ethereal talk.

Frank: My second point is probably even more controversial and again I want to explicitly align myself with Kim here. Many times in my life I’ve said the best job I’ve ever had in my whole life was when I drove a fork lift in an auto factory many, many years ago. And I say that to say, yes workplaces create community. When I worked in a big factory, I very much was part of a community. We had a good time. And we socialized outside of the workplace. There was a connection there that was imposed on us because a factory is a system of enforced cooperation. It brings human beings together and it divides work in a certain way and it creates social as well as economic relationships. But I really think one of the things in this conversation that’s been most valuable to me and I think Barbara said it is – A part of creating community is the work of creating community. Of creating community for the sake of creating community, not treating it as it will be the byproduct of us doing something else. I think I’m understanding that this morning more clearly than I have understood it up to now. it. And I think that is what’s missing from,

14

Marx thought the mode of production alone would recapacitate people and it didn’t. It actually created more individuals.

Frithjof: Well I think the difference between what Marx was talking about and what we mean by community production is huge. I did visit any number of communist countries before I started working on New Work. And I started working on New Work after having spent time in communist countries because they struck me as inhuman. That there was very little compassion. There was no love of work and everyone seemed dreadfully depressed. So I have very little patience with Marx.

Frank: Well I don’t think it’s a question of being patient or impatient with Marx. I think this has been very rich conversation. One thing Frithjof I will say is I don’t have a lot of experience with this but I will say I think Cuba is a pretty good place and in my brief times that I’ve spent there I think there’s quite a bit of compassion and I think there’s quite a bit of satisfaction in Cuba.

Grace: Community cannot grow out of the mode of production. The mode of production is important. We now have a community mode of production but it has to be a psychological, philosophical process taking place alongside of it.

Frank: We have to grow our souls, to coin a phrase. I think we all agree on that. I mean the fact of the matter is that forget whether we like or don’t like Marx at the moment. By certain definitions, admittedly self-proclaimed definitions, I agree with all of those who say the world in the last 50 years has experienced an enormous amount of poverty reduction. But it has come at the expense of what we mean by community for one thing, and compassion and at the expense of the planet and of the resources of the planet. So this balance again between the consciousness of community, for lack of a better way to put it, and the stuff – the food, the objects, the material things that humans need to survive and thrive. If this introduction only makes one point my summation would be that the New Culture is as least as important if not more important than the New Work. Maybe we should seriously think about reversing the words we use here from New Work/New Culture to New Culture/New Work.

Grace: I think that I would recommend our rereading of Chapter 6, Dialectics and Revolution by Jimmy Boggs. He talks about how we’ve put so much effort and energy into production that we have forgotten what we have to do about ourselves.

Frank: OK. I think this is a good stopping point but if anybody wants a last word they should take it.

Grace: I think in the manifesto where Marx says the constant revolution in technology distinguished the bourgeoisie epoch and he ends it up by saying to face with sober senses our conditions of our life and our relations with our kind, we have to do that or face conditions of life but relationships with our kind. If we emphasize new work and not new culture we will be repeating mistakes of the 19th century, of Marx. By emphasizing production over culture.

Kim: When we say the word work first I think that people think about jobs. Work and jobs can be used simultaneously and I think some time people think about the work, I mean they switch the two. So I think if you say culture first it’ll help people understand that the culture has to change in order for the jobs to, the kind of new work that we’re looking for to take care of us to happen.

Rich: So my final comment is what new culture/new work/new work/new culture/mode of production/community production/community culture is all about is what we’ve historically 15

talked about as moving from dialectic materialism to dialectic materialism humanism. Where the role of consciousness and conscious choice and the values are as significant as what we have once called the material world. That there is a new unity being created at this moment in history because technology has advanced to the point where we can actually deal with that poverty in the deepest part of Africa that we’ve fucked for the last 500 years. But you can only do it if you deal with the sons of bitches that like to deal with luxury and greed, and be that 5%. So that’s my final comment. I think we’ll probably continue the rest of our lives with this conversation.

Frithjof: If somebody asks me Frithjof, what is it that you really address? What is the problem that you are really putting in the light? My answer is poverty… How much poverty has been reduced in the last few years? Don’t go by the propaganda that’s being told to you. If you look into India, if you look into Russia, if you look into Africa there’s plenty of poverty. So we do have a difference between us that to some extent is a personal difference. I live a different lifestyle from the life you live. I respect what you’re saying and what you’re doing supposedly. But I’m saying what I’m wanting to do frankly is different because to my mind, there are also people who don’t exactly hang onto my clothes but there are plenty of people who try to get some idea of where to go. So new work. My sense of it is that yes, production is crucial. I get this whole business of which comes first, the chicken or the egg, I find really I don’t know. Should it be first production or first the souls or first the souls or first production? To my mind I find it extremely interconnected and interlinked. I do feel that’s my last sentence. Whatever experience I have had that talking to very very poor people about changing their souls is really creating a situation where they put on their jackets and leave.

Grace: I think the mission of the human is to become fully human. And we need modes of production that make that possible. And now we have modes of production, jobs that make that impossible.

Kim: When I talk about education now, I ask people what kind of education are you talking about, and who’s your audience? So I’ll say, because we use education so general. So I’ll say are you talking about an education about being a parent, are you talking about a street education, are you talking about a formal education? Because we use it so broadly. We paint with this broad brush so when I’m talking to a person they might say, oh well that doesn’t fit me. So I’m glad you said what you said because what I’m talking about when I’m talking about growing our souls, I’m not talking about poor people in countries who have never had any money. I’m talking about those of us who’ve had resources who have not considered others or maybe who actually need to change so we can help the people who haven’t had any resources at all. This is not a one-size-fits-all. So I know what you’re talking about when you talk about people who have never had economic security at all. I’ve had conversations with people who’ve told me, I’ve never had it and I want it! And you’re not going to take it away from me. You’re not going to take that opportunity away from me, you’ve had it before Kim and I want that. So to have conversations with folks and explain to them that I have their best interests at heart and I can just share what my experience has been having some of those things. It’s a challenge to do that but for the record I’m not talking about everybody, only if it fits.

Rich: Thank you. Party’s over! We love you Frithjof, thanks! Long live mode of production, the end of poverty and the revolution to grow our souls! Long live dialectics!

Frithjof: We need more conversations like this.

16

What’s Wrong With

“Old” Work?

The JOB System

The J-O-B system organizes the work of the world in a certain way.

• It offers too much to some and little or none to others.

• It depends on production for the sake of production and consumption for the sake of consumption.

• It compels unequal relationships between employers and the employed. • It is cruel to the unemployed.

• It drives the insatiable destruction of precious natural resources. • It is hostile to the creation of community.

• It is inherently stressful to individuals, families and society. It deforms the entire process of education.

• It politically empowers some to the unnecessary disadvantage of others. • It reproduces entrenched racial and global disparities.

• It promotes conflict rather than cooperation.

• It reqires dishonesty and deceit at every turn, espcially in the marketing of everything

• As currently structured, the global J-O-B system is not only failing – it is a menace to life on the planet. It is a system whose time is past.

19

Is Progress Good for Humanity?

By Jeremy Caradonna

The Atlantic Magazine

The stock narrative of the Industrial Revolution is one of moral and economic progress. Indeed, economic progress is cast as moral progress. The story tends to go something like this: Inventors, economists, and statesmen in Western Europe dreamed up a new industrialized world. Fueled by the optimism and scientific know-how of theEnlightenment, a series of heroic men—James Watt, Adam Smith, William Huskisson, and so on—fought back against the stultifying effects of regulated economies, irrational laws and customs, and a traditionalguild structure that quashed innovation. By the mid-19th century, they had managed to implement alaissez-faire (“free”) economy that ran on new machines and was centered around modern factories and an urban working class. It was a long and difficult process, but this revolution eventually broughtEuropeans to a new plateau of civilization. In the end, Europeans lived in a new world based on wage labor, easy mobility, and the consumption of sparkling products.

Europe had rescued itself from the pre-industrial misery that had hampered humankind since the dawn of time. Cheap and abundant fossil fuel powered the trains and other steam engines that drove humankind into this brave new future. Later, around the time that Europeans decided that colonial slavery wasn’t such a good idea, they exported this revolution to other parts of the world, so that everyone could participate in freedom and industrialized modernity. They did this, in part, by “opening up markets” in primitive agrarian societies. The net result has been increased human happiness, wealth, and productivity—the attainment of our true potential as a species.

Sadly, this saccharine story still sweetens our societal self-image. Indeed, it is deeply ingrained in the collective identity of the industrialized world. The narrative has gotten more complex but remains à la base a triumphalist story. Consider, for instance, the closing lines of Joel Mokyr’s 2009 The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain, 1700–1850: “Material life in Britain and in the industrialized world that followed it is far better today than could have been imagined by the most wildeyed optimistic 18th-century philosophe—and whereas this outcome may have been an unforeseen consequence, most economists, at least, would regard it as an undivided blessing.”

The idea that the Industrial Revolution has made us not only more technologically advanced and materially furnished but also better for it is a powerful narrative and one that’s hard to shake. It makes it difficult to dissent from the idea that new technologies, economic growth, and a consumer society are absolutely necessary. To criticize industrial modernity is somehow to criticize the moral advancement of humankind, since a central theme in this narrative is the idea that industrialization revolutionized our humanity, too. Those who criticize industrial society are often met with defensive snarkiness: “So you’d like us to go back to living in caves, would ya?” or “you can’t stop progress!”

Narratives are inevitably moralistic; they are never created spontaneously from “the facts” but are rather stories imposed upon a range of phenomena that always include implicit ideas about what’s right and what’s wrong. The proponents of the Industrial Revolution inherited from 20

the philosophers of the Enlightenment the narrative of human (read: European) progress over time but placed technological advancement and economic liberalization at the center of their conception of progress. This narrative remains today an ingrained operating principle that propels us in a seemingly unstoppable way toward more growth and more technology, because the assumption is that these things are ultimately beneficial for humanity.

Advocates of sustainability are not opposed to industrialization per se, and don’t seek a return to the Stone Age. But what they do oppose is the dubious narrative of progress caricatured above. Along with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, they acknowledge the objective advancement of technology,

but they don’t necessarily think that it has made us more virtuous, and they don’t assume that the key values of the Industrial Revolution are beyond reproach: social inequality for the sake of private wealth; economic growth at the expense of everything, including the integrity of the environment; and the assumption that mechanized newness is always a positive thing. Above all, sustainability-minded thinkers question whether the Industrial Revolution has jeopardized humankind’s ability to live happily and sustainably upon the Earth. Have the fossil-fueled good times put future generations at risk of returning to the same misery that industrialists were in such a rush to leave behind?

But what if we rethink the narrative of progress? What if we believe that the inventions in and after the Industrial Revolution have made some things better and some things worse? What if we adopt a more critical and skeptical attitude toward the values we’ve inherited from the past? Moreover, what if we write environmental factors back in to the story of progress? Suddenly, things begin to seem less rosy. Indeed, in many ways, the ecological crisis of the present day has roots in the Industrial Revolution. For instance, consider the growth of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere since 1750. Every respectable body that studies climate science, including NASA, the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration, and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), has been able to correlate GHG concentrations with the pollutants that machines have

been spewing into

the atmosphere since

the late- 18th century.

These scientific bodies

also correlate GHGs

with other human

activities, such as the

clearing of forests

(which releases a lot

of carbon dioxide

and removes a crucial

carbon sink from the

planet), and the

breeding of methanefarting

cows. But fossil

fuels are the main

culprit (coal, gas, and oil) and account for much of the increase in

Carbon dioxide (PPM), methane (PPB), and nitrous oxide (PPM) in the atmosphere since 1750. Before the Industrial Revolution, CO2 levels had long been stable at about 280 PPM. Now they’re above 400 PPM. CO2 levels have not been this high for at least 2 million years. (USGCRP 2009)

21

the parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The main GHGs, to be sure, are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and a few others, many of which can be charted over time by analyzing the chemistry of long-frozen ice cores. More recent GHG levels are identified from direct atmospheric measurements.

What we learn from these scientific analyses is that the Industrial Revolution ushered in a veritable Age of Pollution, which has resulted in filthy cities, toxic industrial sites (and human bodies), contaminated soils, polluted and acidified oceans, and a “blanket” of air pollution that traps heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, which then destabilizes climate systems and ultimately heats the overall surface temperature of the planet. The EPA is quite blunt about it: “Increases in concentrations of these

gases since 1750 are

due to human activities

in the industrial era.”

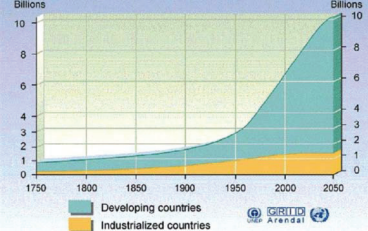

It’s worth noting, too,

that the population of

the world only began

to take off during the

Industrial Revolution. For

millennia, the population

of homo sapiens was

well below the 1 billion

mark, until that number

was surpassed around

1800. The world now

has 7 billion people and

counting. That’s a lot of

Carbon dioxide and methane levels in the atmosphere since 1750. (NASA, based on data

from the NOAA Paleoclimatology and Earth System Research Laboratory)

Population levels in developing and industrialized countries over time, with future projec

tions. (Philippe Rekacewicz, UNEP/GRIDArendal)

22

people who require food, energy, and housing and who place great strains upon global ecosystems. Consider the following figures:

When we take these trajectories into

consideration, the

Industrial Revolution starts to look like

something less than an “undivided blessing.” It begins to look like, at best, a mixed blessing— one that resulted in technologies that

have allowed many people to live longer, safer lives, but that

has, simultaneously, destroyed global ecosystems, caused the extinction of many living species, facilitated rampant population growth, and wreaked havoc on climate systems, the effects of which will be an increase in droughts, floods, storms, and erratic weather patterns that threaten most global societies. All of this is to say that the simple-minded narrative of progress needs to be rethought. This is not a new idea: In fact, critics of industrialization lived throughout the Industrial Revolution, even if their message was often drowned out by the clanking sounds of primitive engines. In their own particular ways, thinkers and activists as diverse as Thomas Malthus, Friedrich Engels, the Luddites, John Stuart Mill, Henry David Thoreau, William Wordsworth, and John Muir criticized some or all aspects of the Industrial Revolution. The narrative of industrial-growth-as progress that became the story of the period occurred despite their varied protestations. The Luddites questioned the necessity of machines that put so many people out of work. Engels questioned the horrendous living and working conditions experienced by the working classes and drew links between economic changes, social inequality, and environmental destruction. Thoreau questioned the need for modern luxuries. Mill questioned the logic of an economic system that spurred endless growth. Muir revalorized the natural world, which had been seen as little more than a hindrance to wealth creation and the spread of European settler societies around the globe.

These figures have provided wisdom and intellectual inspiration to the sustainability movement. John Stuart Mill and John Muir, for instance, have each been “rediscovered” in recent decades, respectively, by ecological economists and environmentalists in search of a historical lineage. For the sustainabilityminded thinkers of the present day, it was these figures, and others like them, who were the true visionaries of the age.

This post has been adapted from Jeremy Caradonna’s new book, Sustainability: A History.

This article available online at:

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/09/is-progress-good-for-humanity/379781/

Copyright © 2014 by The Atlantic Monthly Group. All Rights Reserved.

23

4 Calamities Destroying America’s

Economy Being Ignored by Elites

AlterNet [1] / By Frithjof Bergmann [2]

Published on Alternet (http://www.alternet.org)

The world’s current economic and political structures are proving incapable of fixing the global crisis of poverty, unemployment, and dislocation from a viable way of life for the majority of the world’s population. Why? Let us begin with one present-day example: Larry Summers, former Secretary of the Treasury and also former chair of the Board of Economic Advisors, recently was the principal guest of the national radio broadcast “On Point.” The topic of the hour-long dia logue was growing “inequality.”

Summers posited that we are in an oddly slow recovery. He gave some reasons for the slowness but maintained that the measures instigated by the government (the Federal Reserve pumping funds into the economy, and the like) were fundamentally correct, and that with patience and persistence the recovery would solve the problems we have.

This basically is the position of Obama and importantly, by no means only his. Every government in every country subscribes essentially to this same apostolic faith. That faith is pathetic and even grotesquely mistaken. It ignores the four “Tsunami” causes for the globally increasing inequality:

1. Automation: The number of jobs that have been automated out of existence in the last 30 years is astronomical. Any effort to enumerate them would be silly. Useful, on the contrary, are perhaps a few hints of the kinds of automation that are still in the future, but nonetheless just around the corner. Observe what is happening in retail – Amazon.com [3], and more generally in the service sector, in banks and offices; but beyond that consider the near future of robotics, and close to that the potential of self-driving cars, and of course the galloping field of fabricators. Automation so far has only been the first breeze of an approaching hurricane.

2. A second colossal cause is globalization. Despite the nonstop discussion of that topic its basic significance is still largely misunderstood. That factory work is outsourced to lower wage coun tries is a belittling phrase; more accurate is the contrast between the former monopoly of a very few colonial powers and the now prevailing condition where all countries everywhere — even the Central African Republic and Borneo and Mongolia — are in development. In other words, in all countries people are looking for jobs. Thus the supply of labor has burst through all bounds! This in turn means that the value of unskilled work has plummeted beyond human sustainability much less economic growth.

3. Environmental degradation is growing. The depletion of natural resources is directly caused by fruitless efforts to stem unemployment. Unemployment threatens to grow continuously and the only response we have so far marshaled is economic growth, which self-evidently is coupled to the depletion of our resources.

4. The fourth mega-force that escalates inequality everywhere is the industrialization of farming. Throughout the millennia of the Agricultural epoch approximately 75% of the population lived and worked on farms. That percentage only started to gallop away from this ratio when farming 24

became mechanized. However, in the brief period of less than 200 years a breathtaking transfor mation has taken place. Worldwide 70% of farmers have been driven from their work and their land. In country after country the percentage of people still working and living on farms has thundered downwards so that it is now in some countries only about 4%. On some continents that human migration is still in its headlong tilt: but as villages die, the former farmers do not find work; they are absorbed in slums and sink down in the morass of extreme poverty, violence, crime, prostitution and drugs.

The really foul and grotesque dimension of this lies in its cognitive segregation, for the world wide migration away from the farms is hardly mentioned when the deficit of jobs and the rise of inequality are discussed. In sheer numbers, this is obviously the most gargantuan cause.

It is stunning that there are whole shelves of books about the job-problem, but the reality of the loss of working on farms has rarely been included in the workforce calculations. In essence it means that 75% of the total working population have been cut off from their work and that the need to find re-employment for that huge number is part of the monster-problem that we are failing to even identify let alone solve.

If one adds these four Tsunamis together —automation, globalization, destruction of natural resources and the industrialization of farming — then it becomes obvious that the remedies now applied — stimulation of the economy, raising the minimum wage, more education and the rest — are laughably inadequate. It also becomes evident that we are emphatically not in a recovery, somnambulant or otherwise.

None of these causes are “circular,” or as it is sometimes expressed cyclical, which recoveries by definition are. All four are linear: automation, globalization, destruction of the environment and the migration away from the land will grow, far beyond where they are now, and will multiply. The inequality will become even more monstrous and more dangerous than it is now. The con trast between slums and the palaces of the superrich is already surreal and fantastic, but it will grow further and beyond our worst imaginings. The faith that we are in a circular turning wheel situation, and that automatically, obedient to the laws of economics, we move towards equilib rium, is totally unfounded. It is just a misguided medieval superstition.

We are not turning in a circle; on the contrary we are undergoing a gigantic linear transformation that is as all changing as the shift from agriculture to industrialization.

Why is this a gigantic linear transformation? Because there is no circling back to a former “bet ter” time. The mega-factors listed have produced an enormous rift or a bifurcation. It is a split between the 20%, Oasis people (the rich) and the 80%, Desert people (the poor.) Other groups have of course a greater liking for describing the division as between 1% and 99% but that seems too exaggerated.

New Work New Culture is a new way of looking at and actualizing how people can live in peace and prosperity, working together to provide what is needed not just for survival but for joyous fulfillment. People of good will must stop looking back, yearning for the good old days.

New Work New Culture gives us a roadmap to take on the task to articulate a ladder that defines 25

a practical, performable sequence of steps in detail that is realistic and manageable. By doing so we will not just alleviate the four Tsunami Calamities but give life to a rise, an ascent that has become possible with the technology that we now have.

(Frithjof Bergmann is a retired Professor of Philosophy from the University of Michigan. He has been writing, teaching and organizing for the ideas of New Work for more than 3 decades. He has authored many works, including On Being Free (1977). He is a principal organizer of the New Work New Culture conference [4] in Detroit, Michigan from October 18-20.#NWNC2014 [4]) [5]

Source URL: http://www.alternet.org/4-calamities-destroying-americas-economy-being-ignored-elites Links: [1] http://alternet.org [2] http://www.alternet.org/authors/frithjof-bergmann [3] http://amazon.com/ [4] http://reimagin ingwork.org/ [5] mailto:corrections@alternet.org?Subject=Typo on 4 Calamities Destroying America's Economy Being Ignored by Elites [6] http://www.alternet.org/tags/economy-0 [7] http://www.alternet.org/%2Bnew_src%2B

26

COMMUNITY PRODUCTION: HOW COMMUNITY PRODUCTION CAN REDUCE THE COST OF “LIFE NECESSITIES”

By Frithjof Bergmann

1. FOOD

2. HABITAT/RENT

3. UTILITIES

4. TRANSPORTATION

5. CLOTHES AND SHOES

6. FURNITURE

7. INSURANCE

8. MEDICAL EXPENSES

9. EDUCATION

10.CHILDCARE

Through a great deal of observation, experimentation and testing we eventually arrived at this list of 10 “Life Necessities.” Nothing was ironclad nor universally hard and fast. Individuations and exceptions appeared at every turn. Nonetheless, slowly, a fairly consistent pattern emerged. Regardless even of the continent on which we were examining the lives of people in extreme poverty, despite the multispangled variety, as it were, throughout it, poverty to our surprise seemed relatively coherent and similar everywhere.

Everything depends of course on what one means by this. A first glimmer of specificity enters the picture the minute we say that food is of course the first and most demanding of these “Life-Necessities.” Not surprisingly, some high beam thoughts that connect food with the New Work framework arise at once. How possible is it to reduce or terminate the buying of food and substitute it with growing one’s own. It is interesting, I think, that the hard as nails resistance to this, on its face, so obvious a proposal is a cultural objection. The people that we call “Desert People” do not want to “go back” to the growing of their own food. That was the plight of their ancestors, and returning to it spells defeat and capitulation instead of the positive connotations that well-meaning development workers intend.

Dealing with this is naturally only a first basic step. The reference to or the introduction of advanced hitherto unknown technologies helps to undercut any notion of a “going back” and in that way proves decisively helpful in this as in hosts of other contexts.

In the case of Urban Gardening what is needed for the all-important transition of genuine “Desert People” from the economy of buying to the economy of self-making is that the technologies used for self-making must be fairly advanced and should if possible not resemble too closely 27

the technologies that these people may have used before. That thought is of course shocking to some, especially if one is used to the context of middle class people who add to their luxury and to the burnishing of their self-image the vegetables they have grown on their balcony. Among the examples that illustrate vividly this break from the past in our manifold experience are the “vertical containers” that are by now one of the emblems of New Work. To call them an advanced technology would of course be comical, but that misses the point. They constitute a obvious difference from the gardening of the past and that is what counts. Parallel thoughts apply to greenhouses and most especially to the raising of algae where New Work has emphasized that it is possible to make from algae virtually everything, such as plastics and nylons, for which now we rely on oil.

For the cardinally important transition from the economy of buying to the economy of selfmaking, for that to begin even in baby-steps our list of the ten “life-necessities” is of considerable value. The point has some resemblance to our point about technology. To stress that ten “lifenecessities” constitute a unit that is in a serious sense “complete” has great impact on Desert People. It means that these ten are all that you firmly need, but still more importantly that all you need can be partly made by yourself and need not be purchased, at least not completely. That makes the idea of an alternative economy of selfmaking far more graspable and realistic than it was before. Instead of floundering in a slippery fish-tank of possibilities we can now nail to the wall exactly what we mean: attain a condition

where these ten are self-produced and not entirely purchased and a new and different economy has been reached.

No matter how shabby and dilapidated their habitat is, for virtually all Desert People it commonly is their greatest monthly expense. Therefore the chain that ties them most tightly to the incomemaking life is the “rent” (even if they own their habitat there are costs) they must pay. How very much slum-dwellers often know about the absurdities of normal building is by itself enough to raise one’s estimate of their intelligence. That is one of the many reasons for New Work’s long and determined interest in unconventional, not well-known ways of building, and there again the fascination with previously not encountered technologies asserts itself.

28

A CRITIQUE OF MASS MANUFACTURING as a first step towards New Manufacturing

By Frithjof Bergmann

Few of our convictions are any firmer than our belief that mass manufacturing cannot be surpassed. We have seen countless video clips of cigarettes gushing in something resembling a waterfall from the end of a line, or coke-bottles moving like toy-trains rapidly around curves between small wire fences. So we are dead sure that nothing could be cheaper, or more efficient and modern than that way of manufacturing the products we like. It hits us therefore as an almost shocking surprise that this is not necessarily so.

There is an alternative that is cheaper, more efficient and above all more modern – and vastly more ecologically conserving of nature.

The decisive argument for all this is almost insultingly simple: In a banal way it just highlights the additional costs that on second thought are not external at all.

First and most blatant among these are of course the costs for transportation. If the manufacturing is centralized it occurs in one limited place and then inevitably built into this system the products must be dispersed, and the more extreme the centralization and the wider the distribution the more complex and the more costly the transportation will become. But the sheer movement from the place of production to the place of consumption is just the beginning. The minute that part is recognized and acknowledged the clamor from all the other surrounding costs rises higher and higher. This is a situation where opening the door to the one most insistent and closest factor means that a quickly growing crowd elbow themselves into ever more prominent view. After the variety of modes of transportation, and some might be by truck, others by rail, and still others by boat, there appear inescapably the host of additional arrangements that need to be put into place close to the point of use or consumption. These include the acts of unloading but beginning from those snakes an interminable chain of further provisions from renting the space, and training and paying the salespeople to the great number of precautions and safety assurances that must be arranged, to the lighting that needs to be paid for and not least the food. All of these and still many more, numbers that it would be too tedious to list, are all enmeshed in the far flung network which centralized mass-production requires in order to function.

Now imagine the contrast as decisive and sharp as it can be conjured up, imagine a mode of production that has dispensed with the whole of this clutter, that has thrown the totality of these auxiliaries overboard; a way of producing where one machine, but one of so far utterly unimagined flexibility and capacities for modulation and adjustment, stands as alone as a flagpole and makes a seemingly endless and unlimited variety of products so that the people near it can amble up to it, casually one by one and first describe what they want and then, only a little while later pick it up the new product and start immediately to put it to use. Juxtapose these two ways of making and you have the first glimmer of an idea, of course so far caricatured, simplified, and exaggerated of what New Manufacturing as the next way of producing things will be magnificently superior to mass manufacturing.

29

There is a second very different, sweeping development that also played a large role in shaping the gradual growth of what we more and more call New Manufacturing, the other forward motion is “miniaturization.” The single most graphic and to us most palpable instance of what is happening in the world of the smaller and smaller is the “I –phone” in our pockets, to which week by week if not daily new functions and apps are added into their miniature space. As most of us know, that same shrinking has also occurred with computers, where computers not that long ago filled the space of a room while they now fit snugly into our pockets and beyond that are no larger than a button or even the head of a pin.

The contours of the changes in this direction, not towards the more gigantic and centralized but towards the opposite, the smaller and more dispersed extend of course very much further. It rather recently has taken by storm large parts of the domain of education. The number of the top universities that offer their best courses more or less for free over the Internet is growing by leaps and bounds. This means that one solitary person anywhere, in a valley or on a mountain top, can study everything that has ever been written or choreographed or composed. No need for libraries, or professors, or infrastructure of any kind. I hope you notice the striking similarity to the “exaggerated” “caricatured” picture of a possible future mode of manufacturing I described before.

We do realize that we are technologically many miles from achieving in manufacturing the equivalent to the reality that we already have attained in the kingdom of information: something like full-fledged small factories in individual houses, so widely dispersed that manufacturing could take place virtually anywhere with only the most minimal infrastructure, and in a fashion that would be as autonomous as not long ago was farming.

To articulate this more fully: The New Work Communities’ panoramic picture of where the world now is stresses (as we have said before) four overpowering tsunami-like threats that mountainously roll in from the ocean and descend towards us. The spell-binding contrast is the paralyzing collision between these four mortal dangers and our impotent and witless helplessness in the face of them. We stare at them like a deer blinded at an onrushing car. It is precisely this blindness and this helplessness that in the eyes of New Work is its great challenge and task. This has been our conviction for a very long time, in truth not just for years but for decades. In this long time we have scanned the horizon but also left no stone unturned to find serious, workable, realistic ways in which the four tsunami threats could be not just slowed down, but halted and indeed reversed.

Of course we are eagerly ready to admit that our New Work proposals are often extraordinarily futuristic (which does not mean utopian but just years from where we are now) but that they put forward this one now discussed claim: that just possibly they are the only game in town, that nothing else at all on the table comes even close to having the power. The power to just close the split between the Desert and the Oasis people, let alone avert the other threats, the changing of our climate, the exhaustion of our resources, and the burning out of our culture.

If we now return to the rapidly increasing monster inequality from which we started then we have to admit that the means which we currently employ to heal that bifurcation are lamentably inadequate. We encourage growth, quicker upwards spiraling to still greater productivity, to the making of still more goods. But the fact is that in spite of the occasional talk about the millions in China that have been moved out of poverty, the picture taken as a whole, if one does not allow

30

oneself to be distracted by a bright spot here or there, but insists on assembling out of all the pieces a coherent whole, is dismal. We maintain that the overall picture speaks in any case in glaring colors, and this comprehensive picture leaves no doubt that an approach wholly different from those so far applied is needed with alarm-ringing urgency.

The need for a different approach to production is as plain as the difference between large and small. Mass Manufacturing has become ever more centralized and in line with this ever larger and more massive. The leading conception as an antidote to this is in the context of New Work’s community production and its smallness and associated benefits.

31

Looking Deeper. Thinking Bigger.

By Frank Joyce

Published on Alternet (http://www.alternet.org)

(Note: This article is adapted from “We Are in the Middle of Transformational Change: It’s Time the Debate Matches up with the Huge Challenges Ahead of Us,” published at AltNet.org. in January of 2010.)

A better world is possible. So is a worse one. Which will we get? Finding the proper focus is itself a challenge.

For example, much of the conversation these days is about what the President (or somebody) ought to do about jobs. But isn’t that the wrong conversation altogether?

As it always has been and always will be, there is plenty of Work that needs doing – growing food, moving people and goods around, teaching young people, manufacturing various kinds of stuff, curing sick people and so on. But the 20th century “jobs” method of connecting those needs to individuals, families and communities has been seriously out of whack for quite some time.

What was once mostly a W-2 economy is now a mashed up “system” of W-2, 1099, underground and prison-industrial “employment.” It produces and requires an exorbitant rate of incarceration, massive school dropout numbers, high crime rates and perpetually high unemployment. Further evidence of systemic breakdown is revealed by recent “revelations” that more education does not truly bestow immunity to income stagnation and recurring unemployment. Like it or not, absent a radically different approach, job elimination will continue to outpace the trend toward job creation in good times and bad.

Truth be told, just about all of the systems that sort-of, kind-of solved various problems for the last 200-300 years don’t work all that well anymore. They are out of alignment with current reality.

• Economic globalization under the domination of supranational corporations which incorporates and drives massive changes in science and technology and in the role of nation-states. • Climate change.

• The collapse of the cold war nuclear balance of power. The possible use of nuclear weap ons by countries that possess them, most notably the United States, remains a threat. But now, so does the possibility of their use by nonstate actors like AI Qaeda.

• Changes in the species homo sapiens: human reproduction no longer requires intercourse; neuroscience and pharmacology are increasingly used to modify human behavior, longevity has increased dramatically; our diet is very different; the status of women is drastically altered.

These forces are rocking our planet as it has never been rocked before. All are fast moving. Each is significant.And each one powerfully impacts the others. By way of illustration, consider the nature and role of nation states. “Old” nations such as China are profoundly different than they were less than 50 years ago–never mind 300 or 1200 years ago. The same is true of “middle-aged” nations such as the United States. (The United Nations had 51 members when it was founded in 1945. Today it has 192. Thirty-three nations have come into existence just 32

since 1990. It’s that dynamic that makes even a relatively new kid on the block such as the US middle aged.) But be they ancient or newborns, aIl nations today are struggling to define their relationship to global corporations loyal to no nation-state whatsoever. For the time being, governments are not effectively regulating the behavior and setting the rules of the road for corporations. The BP oil blowout is but one dramatic example.

Yes, the American Revolution created an effective alternative to the tyranny of the British throne. But more than 200 years later our system of government is conspicuously not up to the test of offsetting the tyranny of Big Finance, Big Energy, and Big Health Care.

Naturally, such dramatic change creates noise and confusion. How could it be otherwise? Much of the twentieth-century world order was explained and even predicted by Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, CLR James, Albert Einstein, Franz Fanon, and others. But that has yet to happen for the emerging world order of the 21st century.

There are some exceptions, but mostly what we have instead are “cutting the foot to fit the shoe” efforts by neo cons, neo liberals and neo Marxists alike. None of their theories entirely anticipate or fullycontend with the forces of massive change underway.

So, in the U.S.we hear calls from aI/ points of the ideological spectrum to take America back, recapture the American dream, restore America’s place in the world, “save” this and “defend” that. Elsewhere AI Qaeda, the Taliban and other organizations are also dedicated to restoring a long-gone-and-never-to-return economic, political and social order.

But can the new reality be crammed back into the old assumptions and structures? Is “left to right” the immutable and permanent way of defining the political positions that humans can adopt? Yes,the left-right spectrum retains some descriptive power. But as a genuinely useful tool of analysis, let alone the source for envisioning better ways to organize human activity-not so much.

That is not to say that efforts to start from today’s reality are not underway. Bruce Lipton and Steve Bhaerman in their book, Spontaneous Evolution: Our Positive Future and How to get There from Here; Grace Boggs drawing on the foundation laid with the late James Boggs; Naomi Klein, Jeremy Rifkin in his new book The Empathetic Civilization:The Race to Global Consciousness in World Crisis; the editors and writers at Monthly Review and many others are working to understand, describe and define the forces in play. It is not an easy task. The new reality is extremely complex and the pace of change adds a whole other level of difficulty. That said, perhaps a breakthrough is right around the corner.

Based on what is already understandable, however, one fundamental choice is already crystal clear. Every minute we spend grieving over the loss of the old world order is time we are not spending on imagining and creating the new one.

Does imagining a new world order mean we should give up our struggles to end wars, fight current injustices, and so on? Not necessarily. But the times do call for activists to rethink our collective and our individual commitment of time and other resources. Be it health reform, reinventing unions, improving labor law, ending this or that war-you name it-our problem is that we that we are thinking too small, not too big. In our personal lives, if we are lucky enough to have a car, there are times to devote resources to fixing it as it ages. And then there comes a time to get new one. That is the kind of time we are in now. 33

Another world is already happening. Consequently, another world is not only possible, another world is necessary. The quest of the World SocialForum and the US Social Forum is one prominent manifestation of the search for new solutions and new forms of organization. There are others. Many are turning down the daily noise to focus on the potential for all humans, above and beyond present divisions within and between various nation states, ideologies, tribes, political parties, single issue causes, social or economic classes and religions.

All over the world, some are already reflecting the comprehensive vision expressed by the late peace activist Lillian Genser: “I pledge allegiance to the world, to care for earth and sea and air, to cherish every living thing, with peace and justice everywhere.”

34

Is It Possible to Build An

Economy Without Jobs?

By Frank Joyce

AlterNet | April 29, 2012

Suppose that something caused iTunes, Sony Music, “American Idol,” SiriusXM and every other commercial music entity were to disappear. Would humans still make music? Of course we would. Although capitalists would prefer we think otherwise, human ingenuity created capitalism—not the other way around. And work long precedes the existence of the capitalist system of jobs. Like music and art, work is intrinsic to the human condition. It is essential not just to our survival but to our progress as a species. It is something we do naturally, regardless of the economic and political systems in place at any given time or place in human history.

Of all the systems that contain and define our lives, perhaps the most opaque is the job system. While it is common for us to think about our individual job—or the lack thereof—it is rare that we consider the job system itself. It seems to us that humans have always been either employers or employees — and we always will be. It’s the ultimate TINA (There Is No Alternative).

Who do you work for and what do you do are interchangeable questions in daily social discourse. Parents spend many of their waking hours thinking about how to best raise and position their children so they will be attractive to the person or entity that will “hire” them. From Dlibert to National Secretaries Day, we assume that the job-based system of organizing what gets done, who does what and how our effort is compensated is an immutable component of human existence—almost like air, water and food.

For many, the day-to-day management of the job system is a full-time job of its own. Unions, educators, “human relations” professionals, and many others spend their “working” hours preoccupied with the nitty-gritty of who gets hired, who gets fired, who gets “disciplined,” who gets trained, who gets a raise, who gets overtime, who is entitled to unemployment payments and who isn’t.

Our political discourse is dominated by mostly empty rhetoric of vigorous promises that certain government “policies” will deliver jobs, jobs, jobs. Whatever the question, there is always someone available to say the answer is jobs.

Really? What if jobs are the problem, not the solution? What if the survival of the species homo sapiens depends on imagining and creating a different way of organizing work? What if the job system is inseparable from the tyranny of the 1 percent and the incredibly stubborn persistence of racial inequality?

How did we get this system? What are its benefits? What are its costs? How does the whole system operate to make itself invisible?

Invisibility started with a proclamation disguised as a principle. Adam Smith defined the invisible hand of the market” as “an unseen force or mechanism that guides individuals to unwittingly benefit society through the pursuit of their private interests.”

35

In other words: it’s supposed to be invisible. So don’t even bother looking or trying to figure it out. What you’re supposed to be focusing on is the visible but prominent “achievement” of the invisible hand. Affluence. Prosperity. Technological innovation. Wealth. Men on the moon. Smart phones. Two cars in every garage. Medical miracles. “American Idol.” Mass obesity—oh, wait, that’s off-message.

Truth be told, the job system does coincide with much progress. Many aspects of human existence are enormously better for vastly more people than was the case under feudalism. Over just a few hundred years, millions have come to live longer, eat better, have more leisure time, experience more individual freedom, and become less subject to violence. And that is to name just a few areas of extraordinary development.

At an individual level, millions are satisfied not just with their jobs at the moment, but also with the arc of careers that offered meaningful work and sufficient compensation to afford a lifetime of workplace gratification, affluence and economic security. Presumably those who are content with their place in the job system are inclined to defend it rather than question it.