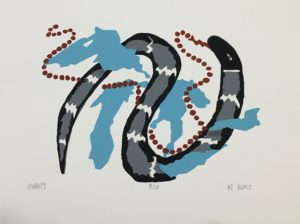

In late summer, I had the honor of traveling to Anishinaabe land (so-called “Northern Minnesota”) to support the indigenous-lead resistance against the Line 3 pipeline being non-consensually built on native land. Line 3 is a tar sands oil pipeline owned by Enbridge, a Canadian pipeline company, that is being built through vulnerable watersheds home to manoomin (wild rice), a centerpiece of Anishinaabe culture*. This pipeline is also routed to cross through the headwaters of the Mississippi River and end near the shores of Anishinaabewi-gichigami (Lake Superior)**.

In addition to the devastating impacts on our climate and the violations of indigenous sovereignty and treaty rights, the introduction of housing encampments for pipeline workers – known as man camps – has led to a localized spike in violence against native women and two-spirit relatives, exacerbating the epidemic known as MMIWR (missing and murdered indigenous women and relatives). The list of why this pipeline project is so detrimental goes on and on; during my time at the frontlines, I learned there are few areas of our lives that this project doesn’t touch and I suggest visiting stopline3.org to get a better understanding of the context and impacts of Line 3.

The things I witnessed during my time there ranged from horrific to life-giving to transformative. I saw police officers with clubs staring robotically at an indigenous matriarch as she described how their support for this pipeline is stealing their children’s futures, unmoved as they brutally arrested those defending the water for all. I experienced being in community with beautiful queer, trans, and two-spirit people dreaming up new ways and honoring traditional ways to care for one another and the more-than-human relatives around us. I felt a groundedness in my being that I had never experienced before as I protected the water that gave me my life, sensing my collective and ancestral self.

The most personal reason I had for joining the frontlines was the threat Line 3 poses to Anishinaabewi-gichigami. I was born and raised in close relationship with this sacred water on Anishinaabe land (Michigan’s Upper Peninsula) and knew that if I wasn’t willing to take risks in order to protect the water that gave me my life, then I did not deserve to be in relationship with gichigami.

I’m a white settler-descended person who has been living on stolen Anishinaabe land for 26 years. Because of the incredible teachers and elders I’ve met on my path, I’m learning what my obligations are to this time, place, and all of the beings who reside here. All of us living in so-called Michigan, and particularly those of us who are not native to this place, have the opportunity to grow our souls in our own struggle against Enbridge’s Line 5, which threatens the land and water we live with as it runs much closer to home, cutting through the upper and lower peninsulas and through our beloved Great Lakes under the water of the Straits of Mackinac.

All waters are interconnected and the borders between states and countries are false colonial constructions. Those of us living on Turtle Island – and particularly on Anishinaabe land- must take part in the struggle against modern-day continuations of colonial powers, exemplified by Enbridge’s violence against native peoples and lands, and be in support of indigenous sovereignty. The resistance to Line 3 and Line 5 are one in the same as they both threaten the waters across Anishinaabe territory and therefore all life; we are all interconnected and we all live “downstream.” This shared struggle gives us an incredible opportunity to create decolonized ways of existing together that include new and old ways, center healthy relationship building as the foundation of a just culture, and heal ancestral pains and woundings while creating a beautiful way of life for future generations. After my time at the Line 3 resistance, I spent time with the lake. When I was first enveloped by the water, I felt an entirely new sense of relationship between us. I was no longer just a child of the water – I was recognized as a protector. (pull out quote) This was the first time in my life I experienced what I can best describe as a sensation of right-relationship. In the shared struggles against lines 3 and 5, we have an opportunity to build right-relationship with the land, water, and beings where we live in whatever ways we are able. We have the chance to learn what our obligations are to this “time on the clock of the world.”

*this information comes from stopline3.org, a hub of information about the resistance to Line 3.

**decolonialatlas.wordpress.com provides context and information about the indigenous place names of the lands we live on.

Author Bio – katey carey (she/her) lives in waawiyatanong with beloved queer and trans kin, learning what it means to belong to place. She is a teacher and walks alongside fellow unravelers of the messy web that is whiteness.