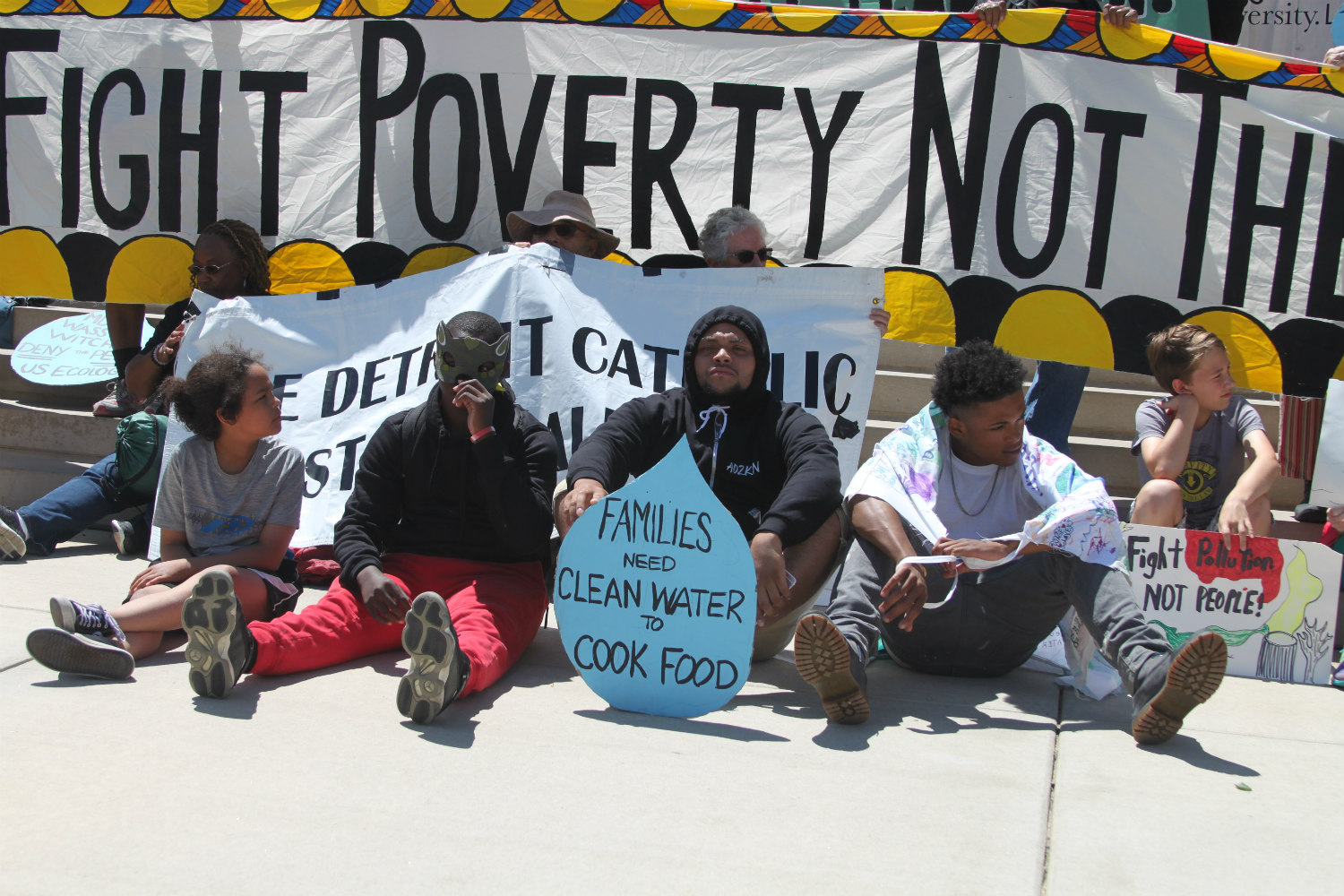

Photos by Valerie Jean

Disconnect Goes Even Further Than Water Shutoffs

by Eric T. Campbell

(interview with Reverend Roslyn Bouier recorded on April 16, 2020)

The shelter-in-place order mandated by the state government was implemented to slow the spread of an all-too-deadly virus. But for those of us already suffering from a lack of access to life-giving essentials, sheltering-in-place has an entirely different meaning. Being confined to a water-insecure household is a life-or-death struggle, pandemic or not. So when we hear from Detroit water warriors that water is being restored at an extremely slow rate, or that in some cases, water is actually being turned off, we see a very different picture than the one painted by city officials.

We know that clean water and proper nutrition are the first and best line of defense against public health crises. Yet many of us lack these basic needs. In communities across the city that have been struggling for justice and basic qualities of life, new questions are emerging. People are asking, “How can we take this moment of suffering and mourning, and move toward self-determination?” These questions are being asked where the struggle against injustice is being fought constantly.

Brightmoor is the area of Detroit with the highest concentration of household water shutoffs. Folks there know best that the coronavirus pandemic only intensifies the daily injustice of seeking clean water. People are still having service shut off. People cannot fight this pandemic without clean water. As a result, people are still being forced to move.

Director of the Brightmoor Connections food pantry and clean water advocate, Reverend Roslyn Bouier, sees the genocidal effects of the water shutoffs continuously. For her, the disconnect between what the city says and what the city does couldn’t be more clear.

“When we look at the maps showing the areas of the city with the highest percentage of water shutoffs, when you lay that map on top of where they’re saying the highest percentages of COVID-19 cases are, they overlap,” Bouier tells Riverwise. “Because, why wouldn’t they? If your water is shut off, that would be the hardest hit population. We’ve just got to tell the truth. To say that there are not that many people left who’ve had water shut off, that’s a lie. There are huge numbers without water. We serve them every day.”

“You took a public resource and you privatized it.” Bouier continues, “So now, we’ve got people whose water is off and it’s still being turned off as we speak. Evidently, a whole new wave of shutoffs just rolled out because yesterday, I had about five to seven people come to me saying, they about to turn my water off; can I get some water so I can have it in the house? They were in tears. They’re turning water off.”

Even with the pandemic in full effect, and with water activists pressuring the Governor to order water turned back on in Michigan, the city has responded with a lack of overall urgency and diligence. Folks have been calling the designated water restoration phone number, only to wait several hours for further instructions. In addition, the recent city reports indicated a relatively low number of households being serviced compared to the total number of calls.

“We’re fighting to get the water on, keep the water on, and for a water affordability plan, right? A plan that’s based on people’s income. Duggan has already said that when the crisis (coronavirus) is over he’s going back to turning off water. They’re not even acknowledging the impact of water shutoffs and the relationship to COVID-19,” Bouier says.

“It always is and always was a public health crisis. We had asked the Governor the week before she declared the moratorium— we sent her a letter requesting that she declare a moratorium on water shutoffs because of the public health crisis because people couldn’t wash their hands, which was the first protocol for protection, safety, mitigation, with covid-19.”

What Bouier and the Brightmoor community, and Detroit are dealing with goes well beyond even the public health implications of ongoing water shutoffs— we are essentially dealing with mass eviction and mass land expropriation for black families. Thousands of black people across the city have faced foreclosure. Rather than just water shutoffs, we have to start looking at the crisis in stronger terms. It is a slow genocide by government policy and government neglect.

“You’ve got to remember, last month at this time, the big news story in Detroit was, the city had overassessed property taxes in the amount upwards of $600 million and that people had been illegally foreclosed on,” recalls Bouier. “Those illegal foreclosures were predicated, and based on water shutoffs. Because remember, if you didn’t pay your water bill it went on to your tax bill. So all those rearranges went onto the tax bills. So people lost their homes.

We’ve got to understand— it’s always been about the land. The water shutoffs— they’ve always been about getting people out of their homes; getting people out of the community; the displacement of human beings. So now what we see is, the water’s not back on, contrary to what they’re saying. They’re also saying there are not that many people without water, that they’ve turned everybody back on.”

We know just how real and devastating the coronavirus has been to families in terms of physical suffering, mental anguish, and economic loss. We are grappling within a health system that cannot support black people in normal times, much less during a pandemic. We have been in some form of crisis in Detroit for many years now. The people fighting the hardest against this injustice must reconcile the fact that the city and state have not even acknowledged that a water crisis exists. Mayor Duggan says he will resume shut off business as usual when the coronavirus subsides. Governor Whitmer has stated that there is no link between water access and public health.

We remain in this stage of divergent realities because our current institutions cannot embrace reparation, on any level, for black peoples especially. They don’t work for us and were never meant to work for us. That leads to the struggle happening on the ground to provide for ourselves, economically, spiritually, culturally, and politically. Out of our grassroots systems for mutual aid, we can rethink and retool ideals that will project us out of systemic oppression— self-determination, community-building, mutual aid— and into a new world.

WATER IS A HUMAN RIGHT!