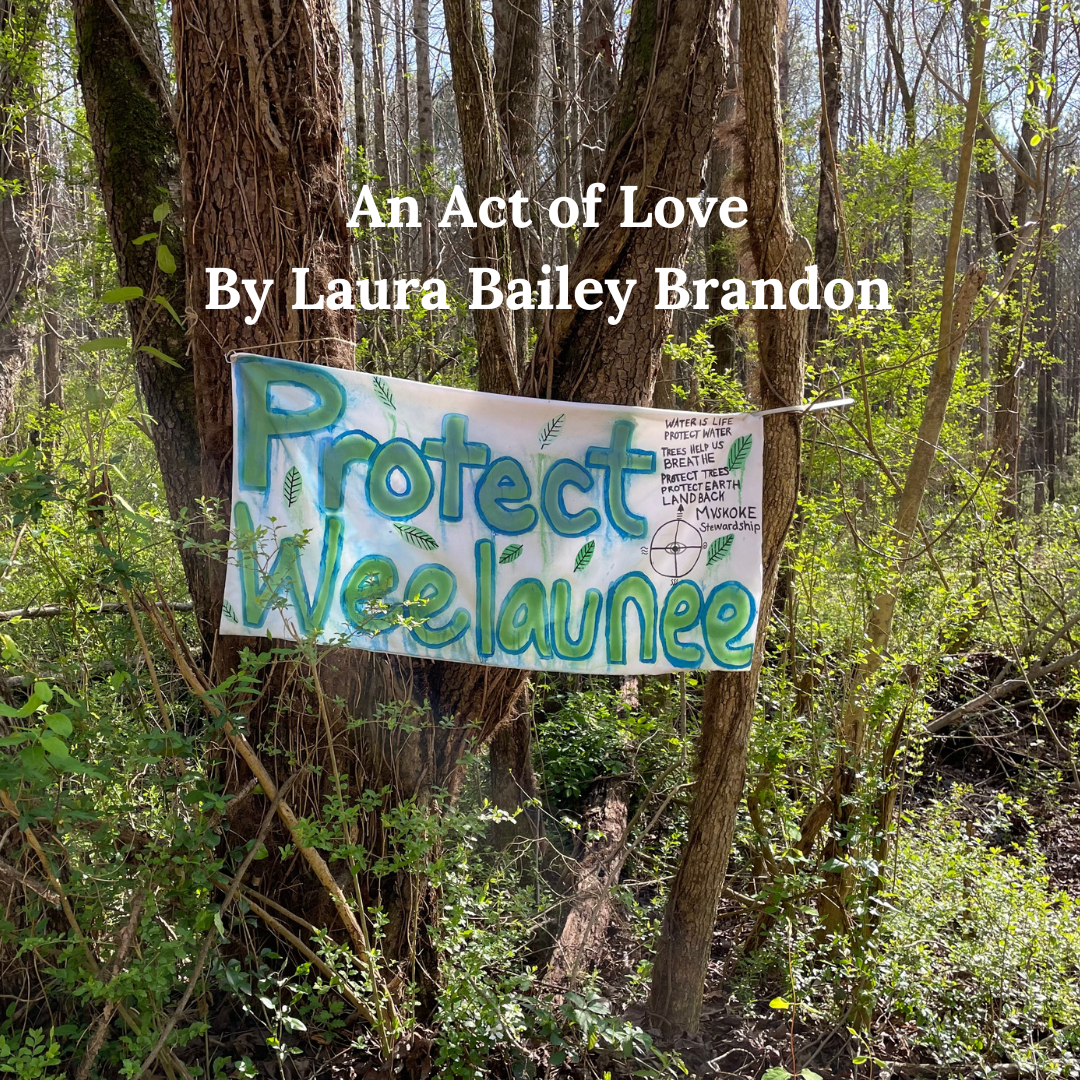

An Act of Love

By Laura Bailey Brandon

We sat on a patchwork of blankets in a field, hugged by trees. We sat facing each other, knees bent against strangers and companions. Twenty-some individuals wrapped in vulnerability and intrigue, one-by-one announcing names and intentions for this action, a cacao ceremony. Led by the words and movements of a soft-spoken guardian, we listened to one another’s needs – hopes for connection, healing, peace and possibility. Fears lifted away by the breeze. Doubt evaporated under a gentle sun. I realized I had forgotten to breathe deeply until we inhaled together, exhaling a harmonious Om.

Above us circled a helicopter. It roared over the forest and hovered above our heads, slashing the air with metal blades and pushing our song to the ground with the force of its sound. We persisted, breathing deeply, releasing fiery pressure through our vocal chords like a choir of dragons. We gazed into each other’s eyes until tears formed and fell to our chins. We removed our shoes and danced in muddy grass with wild abandon, laughing at what the officers in the sky must have been thinking.

After sharing warm cacao and wisdom, we followed a veteran forest defender along a path in the woods. They were showing us their favorite tree, a giant maple they called Mother. Her roots extended beneath us, connected to the land and plants around her. We wrapped our arms around her trunk, holding hands in a quiet circle, listening. The helicopter had left but the threat of invasion by “law enforcement” was always looming.

Eventually the group dispersed among the trees. My partner and I stood under Mother. I played her a melody with the wooden flute I carry – delicate notes climbed her branches. Coral honeysuckle dangled from neighboring trees and rose with the wind like a troupe of trumpets coming to attention. We listened for music and heard their song within. From the old maple, Mother, we followed the trail back to camp, pausing to identify plants and collect a few wild ramps. Their pungent scent carried further by wind, mingled with rich dirt and the aroma of that evening’s vegan dinner.

The camp was a collection of individual tents, hammocks, and DIY shelters, scattered around a communal nucleus – the kitchen, living room and gathering place. A crowd formed in and around the living room where a rabbi sang a Shabbat prayer. People sat, stood, and leaned around him, welcoming the religious diversion. Others stood in line for food, wandered, read, sketched and relaxed, or fulfilled their collective duties. The sun was setting. My partner and I left the cover of trees to see its colors, raising our masks again to protect from possible surveillance drones flying overhead. Back in a nearby field, we sat on a grassy hill watching the hues of the horizon darken.

When we arrived at Weelaunee People’s Park, in Atlanta, Georgia, on Friday, March 10th, the sun was high in the sky. A crew was perched on and under the skeleton of a pavilion they were building, hammering wooden trusses to its frame. Amidst an eclectic mix of trees and broken concrete, cars parked in an oval around an area of grass. In the middle stood the work-in-progress and, next to it, a large pitched tent. A canopy covered an assortment of thrift items marked free towards the edge of the grass. Outside this was the forest and a paved entrance to it, heralded by jagged slabs of pavement. Another canopy tent beside the entrance sheltered a welcome table, water, and other needed supplies like band-aids and trash bags. A forest defender greeted us and offered flyers and reading materials. Although we were well-versed in the purpose for our visit, we asked questions to further our understanding of it.

Why had two Detroiters felt so compelled to travel to Atlanta for the Stop Cop City Movement? Neither of us had heard of the Weelaunee Forest until we started reading about it. Yet both my partner and I scavenged the time and funds to leave our home for a few days and drive 11 hours south, one-way, to participate in a Week of Action that had started with an attack by police – police who had murdered a nonviolent protester two months prior. Leading up to our decision to attend, we immersed ourselves in published pieces and discourse surrounding a struggle that mirrored a generation of injustices. We tallied actions we could take from afar: calling/writing to local leaders and invested parties, informing our peers of the atrocities, researching ways to organize a local event, trying to connect. Yet we felt distanced. We felt that to be better allies and to fully understand what was at stake, we needed to visit the city and the forest – to physically defend a place we tried to vocally protect.

What does it mean to be a peaceful defender? Despite what narrative mainstream media invents, individuals who’ve taken direct action to defend the Weelaunee Forest are nonviolent. The act of occupying a sacred space to prevent construction crews with machines from destroying it is noble. The organizing of events – tree plantings, concerts, dance parties, teach-ins, marches, hikes, workshops and ceremonies, intended to provide learning, joy, community and culture – is an enhancement to people’s quality of life. Even the act of sabotage, the act of damaging physical objects in order to achieve a social objective, is intrinsically harmless to humans. Yet nonviolent forest defenders have been arrested, detained, charged with domestic terrorism, and, in the case of the forest defender Tortuguita, even killed.

That afternoon at the Weelaunee People’s Park, my partner and I sat and played music at the entrance to the forest – he with a steel tongue drum, me with the wooden flute. We placed shakers on the homemade table beside us. Forest defenders with imaginative monikers soon joined in, sharing hot drinks and stories, shaking sound from their palms with the whimsical tunes that our environment inspired. A van arrived later and from it emerged a film crew and the individuals they were filming. A woman with long black hair was their center. She spoke in English and in Spanish to her companions.

The following day we attended a youth rally at a nearby park. We marched through city streets, my partner shaping rhythms on his snare drum, a local organizer keeping beat with a bass, myself playing the trombone – blasts of brass between the people’s chants: Viva viva Tortuguita! Stop Cop City! Defend the Atlanta Forest! Children shouted as they held their parents’ hands. An older woman came out on her porch and clapped. Cafe patrons leaned over patio gates to watch us pass. Drivers, slowed by our procession, honked in support.

After the march, we gathered back at the park. Multiple news outlets were stationed on the ball court in front of a mic, a group holding a banner, and leaders primed with speeches. The woman with long black hair was there again at the center. She spoke in English and in Spanish. It occurred to me that she was Tortuguita’s mother, Belkis Terán, as she sat on the concrete court, legs crossed, hands up and palms inwards, demonstrating how police took the life of her child.

It stormed hard that night. My partner and I made a song as the rain pelted our tent, a song of pain we felt for the forest, and for the life that was lost defending it. In the daylight, fog strung between trees carried a message of renewal. Wisteria hung like Spanish moss, masses of purple swaying and lifted by spring air. Redbud and dogwood, pink and white flowers held high by the branches they bud from, tucked beneath wings of wisteria, beneath a delicate dawn. I remember seeing Belkis apply a coral-colored lipstick. Her son, Pedro, turned to place a hand on her shoulder, checking in. And she, doing everything possible to show the world that she was strong enough to fight. Fight for what her child lost their life for. Fight relentlessly and peacefully for them.