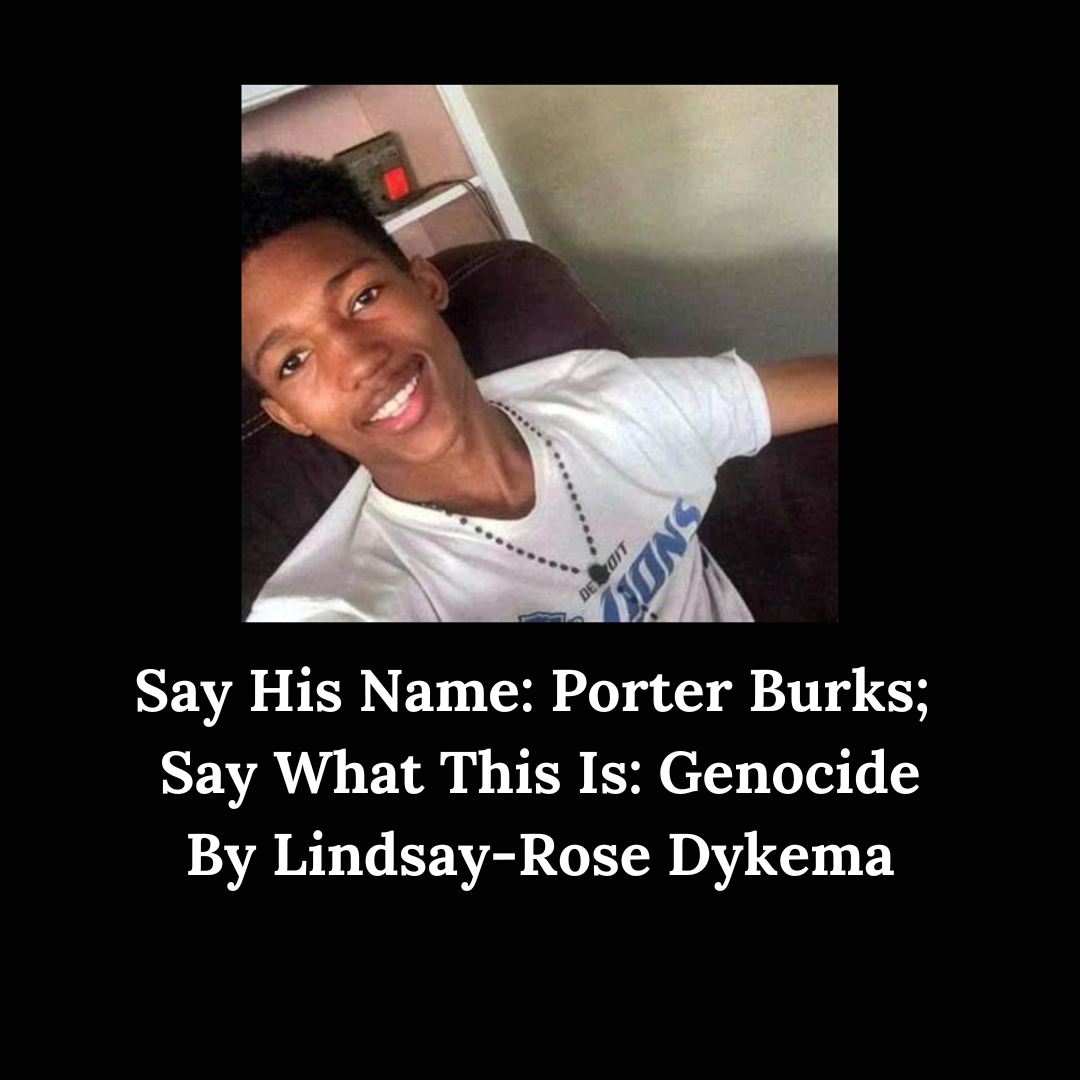

I vividly remember the bodycam footage of the murder of Porter Burks in the early morning hours last October, shortly before settling into my workday as a psychiatrist who works with under-resourced folx in Detroit. I watched a Detroit Police Department (DPD) officer – whose name has not been released – identify himself to Mr. Burks, a 20-year-old Black man with schizophrenia, as a crisis intervention specialist. So much of this story was unimaginably shocking, including the troubling math (38 shots, 19 of them hits; 3 seconds) but my jaw dropped when I heard that part, “He was trained in CIT!” I said aloud to my dark living room.

Crisis Intervention Team training involves 40 hours of PowerPoint slides that a few select cops sit through as recipients of so-called “police reform” measures. These courses are the result of increased funding which has been allocated for police departments, but not mental health services. So, in effect, the officer who murdered a man from 50 feet away – a man who was armed with a pocketknife but so verbally un-threatening that he simply muttered, over and over, “I just wanna get some rest” – is the best the Detroit Police Department has to offer when it comes to helping people in the midst of mental health crises in the city of Detroit.

For me, this tragedy was especially wrenching because a fair number of the people I treat in my mental health practice, Uncaged Minds Detroit, are young Black men with serious mental health conditions. The day after Porter Burk’s murder, one of my patients started his session by asking me about a medical alert card he planned to keep with him moving forward. The card both identifies his mental health conditions and includes an explicit request not to call police. “You saw the bodycam footage?” I asked immediately. “Yes,” he responded. “I am terrified of that happening to me.” I didn’t say this to him, but truth is, I am terrified of that happening to him someday as well.

People with mental health challenges are 16 times more likely to be killed by police[1] and almost half of police encounters involving a civilian death involve someone in a mental health crisis[2]. Furthermore, police are more likely to kill Black people demonstrating signs of mental illness than white people with similar presentations[3]. Extraordinary risk of state-sanctioned violence, therefore, lies at the nexus of mental illness, Black identity, and encounters with law enforcement. As a descendant of survivors of the Armenian genocide and as a Detroit psychiatrist who has borne witness to video footage, time and time again, of Black people with severe mental illness being murdered by even the most highly-trained police officers, I have only these things to say:

Say his name: Porter Burks.

Say what this is: A genocide.

Porter Burks’ name will fade away from media outlets, even after famed Michigan lawyer Geoffrey Feiger shared details like after the shooting police handcuffed Burks and dumped him at the hospital[4]. (DPD reportedly declined to comment on the use of handcuffs on a man who’d just been shot 19 times.) Meanwhile, I suspect the regret his brother likely feels for making the choice to call the police will likely never fade…but what else could he have done? A former colleague of mine who is also mental health professional commented on a Facebook post I made in outrage over the case. She reminded that the mental health system that we are both a part of shares equal blame, Porter’s brother called the police because he had no one else to call. She’s not wrong. As mental health professionals, none of us are doing enough to speak out against the genocide of Black people with severe mental illness.

The sad reality is we cannot count on police and we cannot count on the mental health system. But I have faith in the people. It is my hope that people in my city might someday create a system like the one people in Oakland, CA have put in place over the past year. The Anti Police-Terror Project, a Black-led, multi-racial coalition, developed a replicable and sustainable model for non-police response to mental health crises in communities of color. Through its MH First Oakland[5] project they implemented an alternative-to-911 hotline during the hours that local mental health resources are unavailable by mobilizing peer support and de-escalation assistance.

In the meantime, I will keep telling my clients, my neighbors and anyone who will listen about alternatives to calling the police. I hope to someday develop a mutual aid network among my clientele of about 300 Detroiters, all folx who have struggled with mental health challenges and many who tell me how terrified they are of the DPD. I will keep my eyes open, say Porter Burks’ name and do what I can to call other people’s attention to the terror for which there is no other word but genocide.

For resources and to learn more about alternatives to calling the police:

Visit https://www.uncagedmindsdetroit.com/alternatives-to-911/ or scanning this QR code:

[1] https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/overlooked-in-the-undercounted

[2] https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/key-issues/criminalization-of-mental-illness/2976-people-with-untreated-mental-illness-16-times-more-likely-to-be-killed-by-law-enforcement-

[3] https://time.com/5857438/police-violence-black-disabled/