Photo by lance hicks

Photo by lance hicks

Late one night, Grey received a call from a nurse informing him that his sibling had been forcibly injected with an antipsychotic after an altercation with a staff member. His sibling had been wrestled into a psychiatric ward against their will by armed cops earlier that week; as their emergency contact, Grey spent the next several weeks fielding calls from belligerent staff who constantly misgendered both of them. Somehow, long after he’d fought down the terror of realizing how easily his sibling could be injured or killed by the cops, Grey found himself unable to stop imagining the anguish his sibling must have felt receiving this nonconsensual injection.

While the focus of most public discussion about abolition centers has centered on police and prisons, other systems for dealing with conflict and harm — even self-harm — rely on the same logic of punishment. We need better ways to respond to crises. That’s why we, along with several others, are founding the Detroit Peer Respite.

The experience of Grey’s sibling is not unusual. At the center of carceral mental health care systems lies the psychiatric ward. Voluntarily or involuntarily, some people might find themselves in a psych ward because they’re at risk of harming themselves or someone else. But people are also placed in psych wards because someone thought they were acting “strange”; felt uncomfortable with the way they were speaking, acting, or moving their body; or perceived them to be unable to care for themselves. Severe depression, an intellectual disability, and homelessness are all common reasons that people are placed in psychiatric custody.

The experience can be scary and traumatic, often involving interactions with police, nonconsensual medication, seclusion, and even physical, sexual and emotional abuse. Patients may find themselves subjected to diagnosis and treatment by professionals who disdain them or view them as a threat and might face physical and chemical restraint without their consent. In other words, psych wards work alongside other carceral systems like the police to remove vulnerable individuals from society.

Given the systematic denial of bodily autonomy and individual agency, it’s no surprise that published research consistently demonstrates that the period following discharge from inpatient mental health hospital stays is the highest risk time for suicide attempts — not before receiving treatment, as many might suppose (or hope).

Unfortunately, there are not many alternatives to psych wards for those who feel they would genuinely benefit from crisis support. Alternatives like therapy or counseling can be much less coercive than psychiatric wards but still risk ensnaring people with the police or child protective services because most of these professionals are mandated reporters who are required to report clients if they suspect a threat of physical harm.

Having witnessed and experienced the harms of these carceral mental health “care” systems firsthand, we urgently felt the need for something else. A peer respite is a space where individuals in crisis can receive consensual, non-clinical care from community members who have experienced similar crises themselves.

The peer respite model is widely attributed to Shery Mead and friends in the 1990s. Since then, the model has proliferated across the country; in Michigan, for instance, Still Waters Peer Respite opened in 2022. Despite the fact that the peer respite’s consensual, communal model of care flies in the face of our capitalist and ableist world, peer respites have sprung up in 14 states.

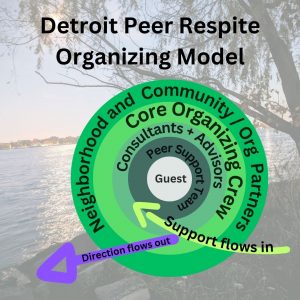

Like these models, the Detroit Peer Respite will rely on a collective of community members who draw on their own experiences of mental health crisis to provide our guests care and support. Unlike many of these models, however, we do not accept government funding. We recognize the state’s role in perpetuating violence against Mad (a term that is being reclaimed by those who suffer from mental health issues) and disabled community members, especially our community members of color. For that reason, we have decided not to make ourselves accountable to these same carceral institutions.

We are mindful and wary that many people have called for psychiatric or mental health treatment as an alternative to the police. As abolitionists, we believe that a world without policing must not replicate coercive systems or their roots in the practice of disappearing some people from our communities, or leaving the care of some folks “to the experts.” The truth is that we must all take care of each other.

In our model, Detroit Peer Respite will host a single guest at a time for up to ten days. During their stay, guests will be supported by the constant presence of peer support workers – everyday people drawing on their own lived experiences to offer companionship, physical proximity, and above all availability to guests experiencing crisis. Rather than attempt to purchase or maintain our own space, we will host guests in a short rotating list of private homes.

We have been working together to make this a reality since spring 2023, when lance hicks called together a small group of folks and shared the initial vision for the project. Currently, we are recruiting volunteer peer support workers (interest form linked at the end of this article) and fundraising (mostly crowdfunding), as we plan to host our first guest in April. We need at least a hundred volunteers to make the 24-hour respite support a reality with 24-hour support.

Detroit Peer Respite Organization Model: This model describes the philosophy we’re using as we set up the Detroit Peer Respite. Photo by lance hicks

Detroit Peer Respite Organization Model: This model describes the philosophy we’re using as we set up the Detroit Peer Respite. Photo by lance hicks

Peer respites are an experiment in building trust and safety outside of the carceral mental health system. They create spaces where lived experience is valued wisdom, where people are trusted to know their own needs best, where groups of strangers come together to help one another survive, and where we invent solutions through collaboration and mutual aid with a disability justice lens.

Centered on a healing justice model, we emphasize consent among all parties in all practices, including amongst ourselves. We do not call the police on our guests. We take a harm reductionist approach to substance use, and guests will never be subjected to police interaction for substance use or any other reason.

We know that everyone commits some harm – including us – and are establishing transformative justice practices to address that harm when it happens.

Our commitment to disability justice means that we require peer support workers to wear masks and for guests to test for COVID at the beginning and end of their stay, and are continuously engaging in community conversations around what prevention and community care should look like in the face of COVID. Any meetings or notes about our guests are also open to our guests.

We hope that guests of the Detroit Peer Respite will always feel that their choices, their needs, their desires, and their bodies are respected.

We long for consensual, noncarceral care to be the norm, not just for mental health crises but for all the ways we interact. In order for that to happen, we need to get comfortable with helping and supporting the people in our communities, beyond our immediate families and loved ones. We hope that our work can build on that of other Detroit organizers to deepen the networks of care that enable us to give our support to our neighbors freely and without expecting anything in return.

Drawing from a tradition of Mad Pride and disability justice, we seek to empower one another to discard the shame and stigma, and to stand in the long tradition of Mad, mentally ill, and disabled people organizing with and for each other. Our work is tied up with efforts to defund and abolish police and prisons. We hope not only to see these racist, carceral systems crumble, but also to see innovative and anti-oppressive alternatives like peer respites flourish in their wake.

Photo by lance hicks

Photo by lance hicks

Calls to Action

Learn more by visiting: detroitpeerrespite.org. To get involved with Detroit Peer Respite by volunteering your time, funds or a special skill, please reach out to at info@detroitpeerrespite.org. To submit a volunteer interest form please visit: bit.ly/detroitpeerrespite. To donate, please visit: https://givebutter.com/peerrespitepilot

***

Grey Weinstein (xe/he/they) is a case manager and Ypsilanti resident. He is passionate about anticapitalist queer organizing, abolition, and trans liberation.

Meghan Krausch, Ph.D. (they/he), is a public sociologist, activist and writer in the Detroit metro area. Their writing has been published in Truthout, In These Times, Inside Higher Ed, and The Progressive, among others. They have been involved in a range of community movements including anti-eviction movements, free schools, independent media, and Latin American solidarity work, and are currently facilitating the Abolitionist Book Club, an inside/outside reading group with members of the Black Prisoners Caucus.

lance hicks (he/him) is a mixed, Black trans femme, a lifelong Detroiter, and an organizer of 20+ years. Since 2005, lance has worked to support movements for justice across multiple domains, but particularly via queer and trans youth organizing, racial justice movement work, and trans care and liberation. He runs a small therapy practice offering abolitionist trauma treatment for community members holding oppression experiences.