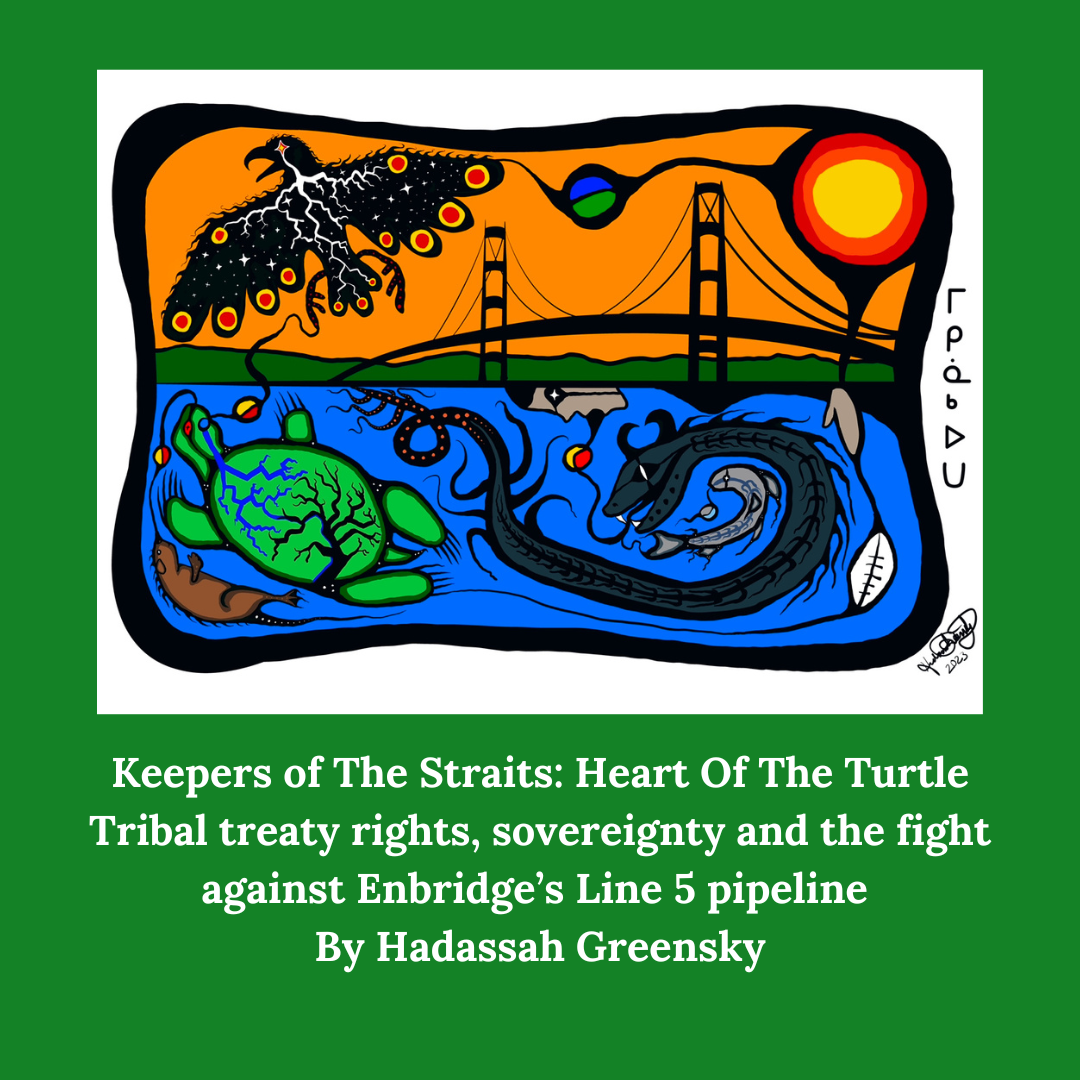

Keepers of The Straits: Heart Of The Turtle: Tribal treaty rights, sovereignty and the fight against Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline

By Hadassah GreenSky (Little Traverse Bay Bands of Chippewa and Odawa Indians)

This piece named, Mikinaak-ode, is a story of the last battle of the great snake and the thunderbird. Original artwork by Hadassah GreenSky

As Anishinaabek of the Great Lakes, we have been here for a long time. The land my ancestors came to know, now present day Emmett and Mackinac County in upper Michigan, was a land once filled with massive white pines, white birches, and a plethora of berries. Waganakising, The Land of the Crooked Tree, or as the French called it- L’Arbre Croche, is now a land largely clear cut and far removed from the original landscape my ancestors knew. Remnants of Anishinaabek resistance in the form of twisted branches remain scattered across the region, a tactic used to protect our tree relatives from the unceremonious harvesting for white man’s profit, deeming several trees unfit for lumber.

The land, taken from our ancestors about 7 generations ago through manipulative tax evasion claims, stretches from the coastlines and surrounding areas of Charlevoix and Little Traverse Bay, up through the straits of Mackinac.

Each family in our territory belongs to a clan; each clan has a duty to uphold certain responsibilities. My family’s clan is Mishiikenh Dodem or Snapping Turtle Clan. Our duty is to be the dreamers, the medicine people, the stargazers, and the water keepers. Our elements are the dirt, the mud, and the water. Each clan had a territory within the tribe. Our territory was the straits of Mackinac, which means place of the turtle, a sacred site for Anishinaabek. We have been care-taking for the straits for generations, but due to colonization, much like the trees that once populated our ancestral homelands, many of us, myself included, were cut off and scattered away from our traditional roots.

It was in 2016, while I was studying jazz voice at The New School in New York City, that I learned of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protests. DAPL, which now runs through sacred Lakota land, threatens the tribe’s water supply. Watching the brutalizing of our people at Standing Rock by police and hired security, I realized just how skewed the US colonial system was against Native people, the land and the water. Standing Rock was a wake up call for many of our Native people on Turtle Island.

As I returned home to Michigan, I was made aware of the Line 5 pipeline by Oil And Water Don’t Mix, a coalition of Michiganders and allies fighting to shut down the 70 year old pipeline. I quickly immersed myself into awareness work surrounding the pipeline, not knowing at the time it has always been my birthright clan duty to protect our waters.

An elder woman from my tribe once told me of an old Odawa prophecy, the story of the last battle of the snake and the thunderbirds. The black snake would come to poison our waters but would unite our tribe as never before. This has come to pass in 2021, all 12 federally recognized tribes came together to write a letter to President Biden, imploring for a stop to the pipeline as it violated several of the international treaty rights of the Anishinaabek. These are the very treaties that formed our political identity as sovereign citizens of sovereign nations, and also the treaties that forced us to cede our beloved territory. Today there are 51 First Nations and Federal Tribes in solidarity calling on Canada to put an end to the Line 5 pipeline.

The first treaty signed between my people and the US government was the Jay Treaty in 1794, 200 years before my birth. This particular treaty gives all Natives freedom on the land, that no whiteman can order us off the land, and that we have ceremonial, fishing, and foraging rights from 16-99 feet around every waterway.

The Straits of Mackinac is the epicenter of tribal fishing in our Great Lakes territory- the place where our sacred whitefish hold their breeding grounds. An unusually powerful area, the Straits have a current that flips 180 degrees around every 3 days. It is a place of ceremony and prophecies.

Presently, the Straits of Mackinac, which connects Lake Huron to Lake Michigan, is threatened by the Line 5 pipeline. The pipeline, built in the 1950s, is operated by the foreign oil company Enbridge and runs underground through the most vulnerable point of the Great Lakes. The University of Michigan Water Center states it would be the worst possible place for an oil spill. The Great Lakes itself holds 21% of the world’s fresh water with a diverse ecosystem that both animals and humans alike rely on to survive. Enbridge has proposed a 17ft diameter tunnel to encase the already outdated pipeline. However, the foreign oil company has a reputation for pipeline bursts, causing the largest inland oil spill in history in Kalamazoo, Michigan in July of 2010 with the Line 6B pipeline, as well as two massive Line 5 oil spills near Lake Gogebic, in Michigan’s upper peninsula. The proposed tunnel is expected to take 6-8 years with drilling up to 300 ft below the straits. Enbridge has reported there will be no negative impact on the ecosystem.

A coalition of Michiganders and tribal governments have come together to oppose the Line 5 pipeline, including Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel, and all 12 federally recognized Anishinaabek tribes of Michigan. As Native Americans holding tribal sovereignty, we are not an ethnicity but a unique political identity with rights ranging from US federal protections to international treaty law which far supersedes state and federal rights.

In November of 2020, Governor Whitmer revoked the permit for the easement that Line 5 sits on, calling on the eviction of Enbridge and their pipeline which gave them 6 months to shut down the line. After 6 months passed, Enbridge did not budge and the state proceeded with a lawsuit. Enbridge then invoked a 1977 treaty stating the free flow of energy products between the US and Canada, which took it out of the states jurisdiction and into federal jurisdiction. This overly broad reading of the 1977 treaty put it in direct competition with the federal rights of the tribes, putting us in a long “waiting-game” in the federal courts and out of the hands of one of our biggest allies- our state governor. However, upholding tribal sovereignty is the checkmate to a long chess game between water protectors and Enbridge, and Enbridge knows it. Enbridge has even attempted to undermine our efforts by using one individual tribal member who aligns with their mission as if their voice can compete with the resistance of 51 Sovereign Tribal and First Nations.

Enbridge and Energy Transfer were also involved in a Texan court case to end the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), with their lawyer working pro-bono with co-defendants to overturn the 1978 law. If they would’ve won, it would have had the potential to put cracks in our tribal sovereignty. On June 15th, 2023, the Supreme Court ruled to keep ICWA intact, in a huge victory for tribal sovereignty. The same week, The Bad River Reservation won their lawsuit against Enbridge, which orders the section of pipeline that runs through the reservation must shut down and relocate within 3 years

Our tribal nations have been successful in the past at upholding our rights, in 1970, the state of Michigan told tribal fisheries they were no longer allowed to use gill nets and had to adhere to standard fishing rules. A relative of mine, Pine Shomin, testified and stated that the 1836 Treaty, if violated, states the waters will rise and take back over the land. The Bay Mills Tribe, backed by The American Indian Movement, resisted and took the matter all the way to the Michigan Supreme Court and won. Tribal sovereignty prevailed yet again. And, so we continue to fight and hold hope.

It is a unique time for Natives as our voices are finally coming into the spotlight within environmental circles. We hold the old earth-based practices that propelled forward sustainable living and care and harmony with the land. We also hold tribal sovereignty, with it the international treaty law and federal legal protections.

As the seventh generation away from the colonization of our territory, I have chosen to walk backwards on the trail my ancestors walked, to pick up what was left behind by the ancestors. We call this concept Biskaabiiyang, or moving forward by looking backwards. This is how we return to the old ways of the Earth, this is true indigenous futurism.

As poet John Trudell said, “Remember the people have always struggled to live in harmony, in peace.” It’s up to us. The fight is still going on. Each resistor to the pipeline is a twisted and crooked branch in a long line of resistance. And we will not give up. We have come too far to give up now. Let them never forget Waganakising was founded on resistance.