Let’s remember their names.

Erma Henderson (1917-2009)

Mel Ravitz (1924-2010)

Maryann Mahaffey (1925-2006)

Ken Cockrel, Senior (1938-1989)

What does a caring, committed, activist local electoral leadership look like? What can we learn from our past to help us make decisions today? We often hear the phrase “we stand on the shoulders of our ancestors.” But who were they?

Detroit is a movement city where activists created ideas and practices of revolutionary organizing that echoed in the elected arena. At the beginning of the last century, the labor movement was born here and influenced a progressive atmosphere to limit capitalist practices. The Black Power Movement of the 1960s-1970s was expanded by vibrant artists producing music and poetry that has made our city known throughout the globe. We are a city remembered for the rebellion of 1967, and the historical and radical writings projecting new ways of thinking about our past and our future. The organizing of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Workers, The Republic of New Afrika, the Black Manifesto, and the Manifest for a Black Revolutionary Party all offered new values, programs, and practices for living in a society that emphasized the wellbeing of people based on justice.

The movements provided the energy for new kinds of elected leadership. Coleman Alexander Young became the first African American mayor and was elected with a strong critique of police brutality and corruption. He found ways to redistribute land through a farm-a-lot program that helped spark the urban gardening movement. He worked with the City Council to find ways for people to stay in their homes, repair them and strengthen their neighborhoods. Often some of the most imaginative thinking came from our elected city council that encouraged neighborhood power, limiting corporate influence, and educating people.

There are four city council members whose legacy from the 1960s and 1970s still matters to me. I often worked closely with them in my journey as a community labor activist. When I moved to Detroit in 1970, Detroit was essentially 50% white, 50% black, with a growing Arab American and LatinX population.

As election 2021 approaches, we know our votes matter. It is time to elect council members who do not fold under pressure, make backroom deals, believe that the corporations and tax cuts will save our neighborhoods. These four council members would never have been silent in the face of water shutoffs, foreclosures, tax scams, and corporate giveaways. They would not have been silent as our city becomes a playground for the white and wealthy. They would never have assented to meetings that limit the voice of people to one minute. They saw democracy as deep, thoughtful engagement about things that mattered locally and internationally. They took stands, differed with each other and other officials and political powers; but each struggled to find ways to create a city that served its people.

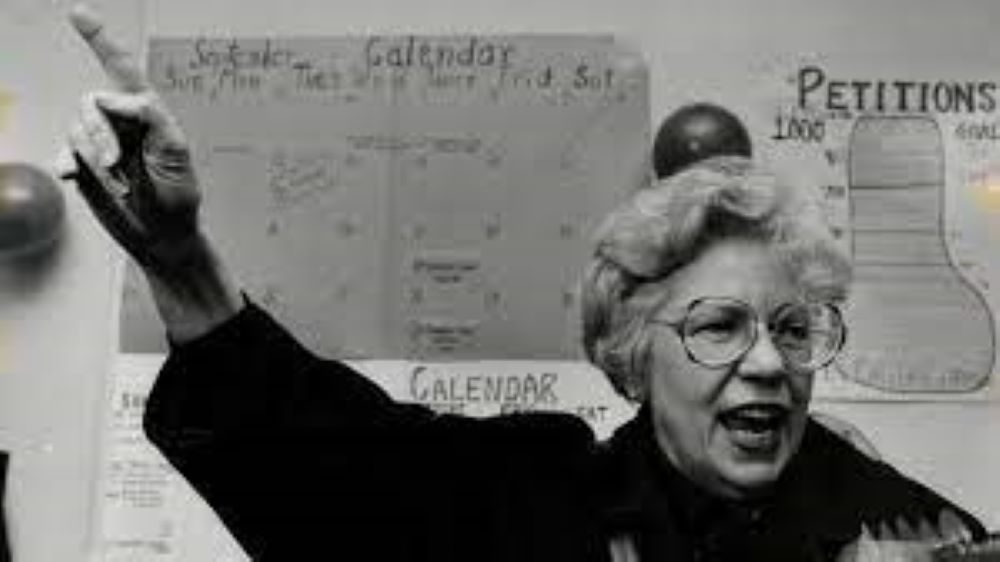

We remember Erma Henderson

Detroit City Council, 1972-1989

Detroit City Council President, 1977-1989

Henderson was an organizer and activist before becoming the first African American woman on City Council. She was also the first African American female City Council President. She was known for her efforts to desegregate the bars and restaurants on Woodward Avenue. She became the executive director and guiding force of one of the largest organizations in the city, the 250,000 member Women’s Conference of Concerns. Erma Henderson used her role on City Council to uplift a progressive, value-based politics.

She was born in 1917 and moved to Detroit in 1918, where she was raised on the east side in Black Bottom. She was a colleague and friend of Coleman Young’s. They attended public school together. Henderson organized her elementary, middle, and high school students to oppose racism, demanding opportunity and respect for every student. She managed City Council campaigns for Rev. Charles Hill in 1945, and William Patrick in 1957, helping Patrick to become the first African American elected to City Council since the 1800s.

Following the rebellion of 1967, she became the Executive Director of the Equal Justice Council, which collected judicial data in an attempt to monitor the treatment of African Americans by the judicial system. In the 1950s, she marched and picketed to ensure African Americans gained admittance to hotels and restaurants. She organized the Michigan Statewide Coalition Against Redlining to take on the state’s banking and insurance interests and was directly responsible for the state’s anti-redlining law, one of the most comprehensive in the nation.

Henderson was a local internationalist. As Michigan’s ambassador for peace and justice, she addressed the World Peace Council on disarmament in Helsinki, spoke out against apartheid at the United Nations, attended a presidential briefing on the Panama Canal, and participated in international women’s conferences. In 1982, she organized an International Trade Conference for the Michigan Chapter of the Continental African Chamber of Commerce, bringing together ambassadors and ministers of finance from 23 African nations to work on trade packages. Erma Henderson’s ally and dear friend was Maryanne Mahaffey.

We remember Maryann Mahaffey

Detroit City Council, 1973-2005

Detroit City Council President, 1990-1998 and 2001-2005

For Maryann Mahaffey, making the world a better place was a life mission. Through her lifelong journey of leadership and advocacy for people, she lived as an example of what social work at its best can be about: fighting for economic and social justice for everyone, especially those who are vulnerable. Her effectiveness as a public servant and agent of change was immense.

Maryann’s early work at a Japanese American relocation center, which she described as a “concentration camp without the ovens,” ignited her zeal to use her social work skills to advance human rights.

From 1965 to 1990, Maryann Mahaffey was a professor of social work at Wayne State University. She served 12 years as Detroit City Council President and 32 years as a Council Member. She was an author, educator, civil rights activist, volunteer, and political leader at local, state, national, and international levels for nearly sixty years, putting into action her deep commitment to solving critical social issues.

She was a champion for women’s rights, filing the precedent-setting lawsuit which established a woman’s right to run for office using her birth name, leading the fight to open the doors of the Detroit Athletic Club to women, and she enacted an ordinance explaining and prohibiting sexual harassment of city employees.

She co-chaired the Detroit Women in AIDS Project, and she was instrumental in the founding of the Detroit Sexual Assault Center. In 1994-95 she chaired the Michigan delegation to the Non-governmental Organizations section of the United Nations’ Fourth World Conference for Women held in Beijing.

We remember Mel Ravitz:

Detroit City Council, 1961-1973 and 1981-1997

Mel Ravitz served on the Detroit Common Council starting in 1961. He served as president of the Council from 1969 to 1973. In 1963 Ravitz joined forces with William Patrick, the only African-American on the Council, and introduced an Open Housing Ordinance. The ordinance would have outlawed racial discrimination in housing. The ordinance failed. The discriminatory law enacted in its place, which Ravitz opposed, was eventually found unconstitutional.

Ravitz understood the importance of community power and was active in the formation of block clubs across the city. In 1973 he ran for mayor against Coleman Young and was supported by the UAW. Ravitz lost the election in part because he supported the police policies, including STRESS (Stop the Robberies Enjoy Safe Streets). Coleman Young called for its abolition. In the early 1980s, Young and Ravitz were again on opposite sides, this time over the issue of the destruction of the Poletown community to build a General Motors Cadillac plant. Mel Ravitz joined with Ken Cockrel in opposing the building of Poletown and the forced removal of more than 5000 residents.

In the mid-1980s, the Boggs Center worked closely with him in organizing against Casino gambling and for local community enterprise. Ravitz became a force for clear, accountable decision-making, encouraging policies to govern the ethics of elected officials.

We remember Kenneth Cockrel, Sr.

Detroit City Council, 1978-1982

Ken Cockrel embodied the spirit of revolutionary leadership in joining movement resistance with local, national, and international organizing. Kenny Cockrel was born in 1938 and died too young at 50 years old in 1989.

Ken Cockrel was a revolutionary, a lawyer, a fighter for the people, who challenged the corruption and racism of the UAW. He helped form the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Black Workers Congress, and the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, which demanded the auto plants. He also helped create the Motor City Labor League, which was a multi-racial popular organization that was instrumental in challenging STRESS and fighting police brutality. To run for Council, he created the Detroit Alliance for a Rational Economy (DARE) that provided intellectual and practical support for his effort. Its core programs advocated for community control of basic necessities and institutions.

As a city council member, he struggled against tax abatements for corporations, schooling people in the destructive power of capitalism, and explaining how corporate commitment to profits at all cost was endangering all of us. He fought consistently in plants and in the community to enhance our voices and sense of dignity.

Democracy is our responsibility. To create caring communities for safety, education, work, where every person regardless of ability or disability, age, ethnicity, race, or gender can reach his/her/their potential requires all of us to be active citizens.

When you vote in the primary, remember: Elected officials can help or hurt our journey. Here are some things to ask of potential candidates.

What is your position on land use?

Are you in favor of the right to water and basic utilities?

Do you support a water affordability plan?

What do you think should happen to protect people’s homes, to protect neighborhood housing?

Where does safety come from? What do you think about moving money away from police practices and toward community programs?

What kind of public education do you see?

Elect city council people who understand that they are responsible to our vision, our concerns, and not their agendas.