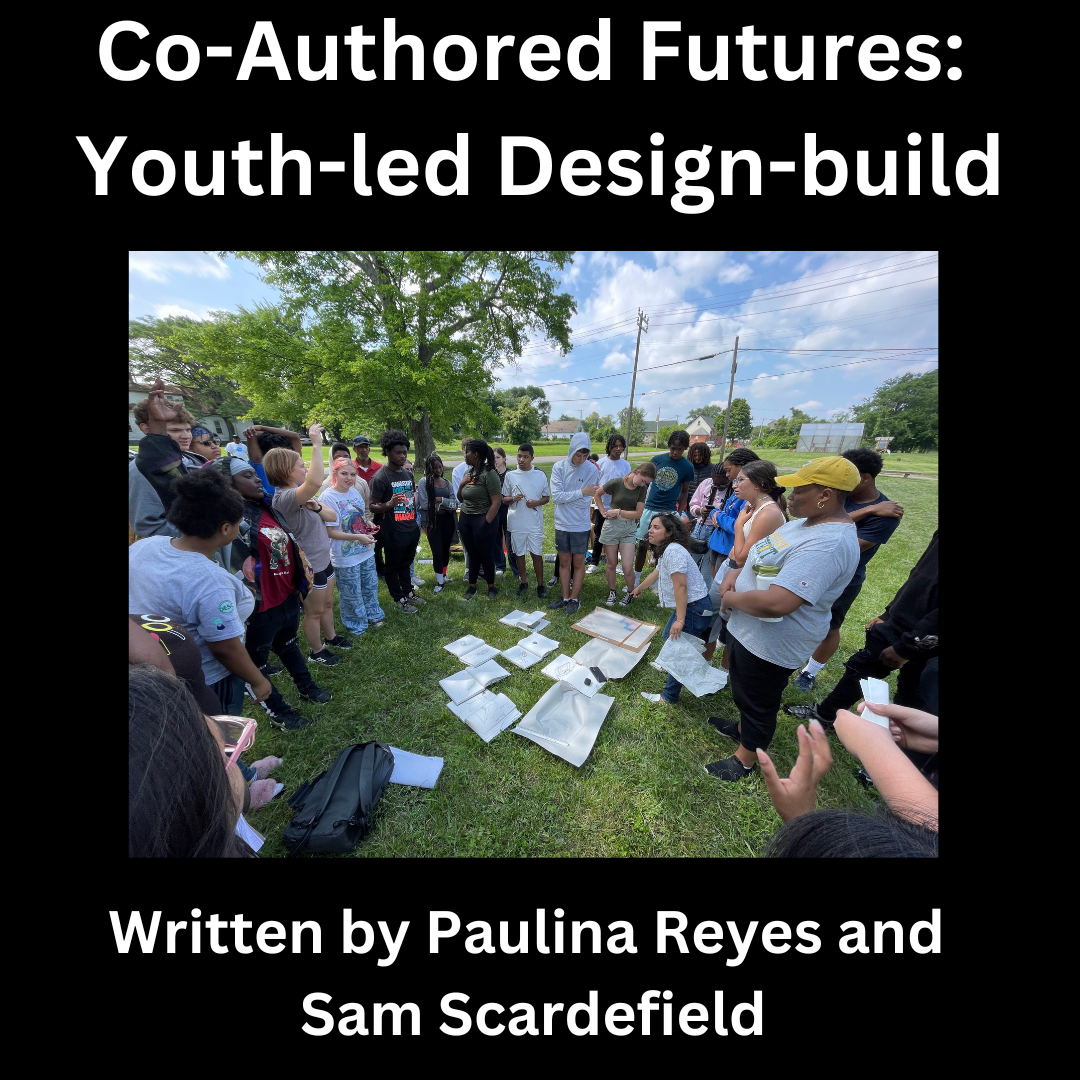

On a cloudless summer day in late July, twenty high school students attending Lawrence Tech’s summer architecture camp board a bus from the LTU campus in Southfield bound for Detroit’s east side. Upon arrival, students file dutifully, if tentatively, into the James & Rose Robinson Community Center, clutching sketchbooks, markers, drawings boards, and rolls of sketch paper. They are there to meet their creative partners for the afternoon, twenty teens and young adults hosted by Freedom Dreams, a Detroit-based organization through which the cohort has been learning practices in neighborhood regeneration. Although hosted by separate programs with their own respective agendas, both groups are present with the same goal: to design and build a small gathering pavilion. Over the course of a single afternoon, the group will have brainstormed a diversity of design solutions, presented their ideas back to one another, and collectively decided on an overall design direction. Three weeks later, that design will stand on the grassy site, the product of an entirely youth-led process.

We are living in a time in which “collective action is a precondition for our continued survival”1. Design education provides a powerful, if underutilized platform for forging new coalitions and protocols of collaboration, enlisting young people to examine how complex social issues are manifested in the built environment – while leveraging cross-sector alliances to co-realize built responses in public space. In other words, design brings together mutually supportive teams which mirror the kinds of alliances necessary to tackle the complex issues of our time. Through this strategic partnership between Freedom Dreams and LTU summer programming, we hoped to choreograph this exchange on a micro-scale, allowing youth the opportunity not just to ideate but to actualize, and ultimately steward their own ideas together.

LINKING OUTREACH & DESIGN

Freedom Dreams is a coalition of organizations and individuals who are helping to create a beloving community on the east side of Detroit by building safe spaces, growing food, and developing new affordable housing based upon universal design so all human beings – with and without disabilities – can reach their potential. Freedom Dreams partners with youth, elders, volunteers, artists, and organizations such as Feedom Freedom Growers, Birwood House, Sweet Water Foundation, The James and Grace Lee Boggs Center, Brightmoor Makers, to weave a fabric of public spaces together, remediating public trust, collaboration, and enact community visioning.

Every year, Freedom Dreams hosts a group of teens and young adults from Grow Detroit’s Young Talent (GDYT) to participate in a summer program based on the principles of neighborhood regeneration. Their routines consist of group reflections, beautification, gardening, and design-build carpentry.

Lawrence Tech’s academic summer camp hosts high school students in week-long programs across a variety of STEAM professions. Dedicated sessions in architecture teach students the foundations of architectural representation and drivers of the design process, culminating in a small design prompt reviewed at the end of the week.

Early conversations between the two program leads revealed opportunities to thread the initiatives, combining LTU’s final design prompt with the Freedom Dreams capstone build: the re-creation of a vacant neighborhood lot into a recreational space through the realization of a small gathering pavilion. The structure would be utilized by ComeUnity One Stop, an organization within Freedom Dreams founded and run by Jasmine Noble, a mental health counselor, whose goal is to provide wrap-around social services for families and youth.

STAGING THE WORKSHOP

On the day of the workshop, the forty young people were divided into teams of four (two members of each group) and spread out on the site. Together they fostered conversation, debate, and creative solutions for the design prompt. This meeting of the minds led to small revelations.

Mariam Nassuma, a rising college freshman and attendee of the LTU summer camp describes how the workshop re-shaped her design approach, situating their ideas in real-world constraints:

“When we were talking about materials, a lot of us from LTU were really disregarding what materials we could use. We started throwing out ideas and they were like ‘we don’t have access to metal, we don’t have access to concrete slabs’…They gave out great ideas which also made me more interested in the project and made us look at it from their eyes.”

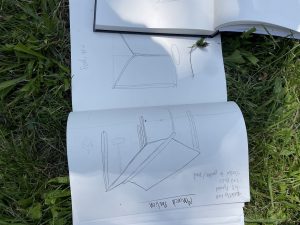

After roughly an hour of dialogue, each team presented their ideas to the group at large. Students gathered their sketchbooks in the grass, and held a vote on the concepts that they were most interested in pursuing, coalescing around ideas like rainwater capture, butterfly roof design, and the inclusion of a conversation pit, concepts which were later hybridized into the final design.

The final structure was named the “Mariposa Pavilion” based on the distinctive folded ‘butterfly’ roof which both provides shade and acts as a simple rainwater catchment system. At ground level, the wooden deck incorporates a universal design ramp for easy access.

FROM IDEA TO BUILD

Once the design was translated into working drawings, Freedom Dreams got to work. In teams of four, youth laminated 2×8 beams, cut half-lap and cross-lap joinery, and screwed and bolted together beams and posts to make bents or wooden frames.

Youth began to dig the foundation for the pavilion, literally exposing an uncomfortable truth in Detroit’s history.

When the city filed for bankruptcy in 2013, government officials appointed an Emergency Manager (EM) to streamline solutions to the economic crisis. By 2014, the EM of Detroit declared a blight emergency whose protocol was similar to that of slum clearance in the early twentieth century. Homes were being demolished by contractors who were not monitored or trained properly. The foundations of the home were not removed and the remains of these century old houses were buried within their foundation walls, covered by dirt shipped into the city.

As the youth hit a foundation wall, they dug wider, only to find rubble preventing them from digging to the depth they needed. It took an entire day to bust up the foundation wall deep enough for the bent to be placed. Everyone chipped in by swinging sledge hammers, pic-ax, shovels, and moving wheelbarrows to overcome such negligence. Finally, the old foundation was cleared to make room for the new. Bents were hand-raised and decking assembled with skills youth had now honed over multiple building projects. Within three days, the pavilion was complete enough to be occupied.

As a team, participating youth had to contend with the past histories of the land in order to chart their own vision forward, emblematic of the current state we find ourselves in as a society. James and Grace Lee Boggs would always ask us “What time is it on the clock of the world?” Today, we are ever more in tension between our past and our future.

Jasmine Noble, founder of ComeUnity One Stop comments on the success of the collaboration:

“What is super awesome is how young people collaborated together, and were able to take something abstract and bring it to reality – discussing, drafting, and building. When they come back, it is my hope they will feel a sense of pride in how they contributed to the neighborhood.”

CLIMATE JUSTICE BY DESIGN

Our present-day world is said to be the age of “VUCA” – Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity. The evolving climate crisis is but one profound example of VUCA in action. Climate change supercharges the conditions of VUCA while upending conventional paradigms for reckoning with its impact. As philosopher Timothy Morton writes, “The environmental emergency is also a crisis for our philosophical habits of thought, confronting us with a problem that seems to defy not only our control but also our understanding”2.

As designers and builders, we are poised to foster truly participatory spaces that stage new understandings and usher ideas into reality. In this, youth-led community building becomes a vital staging ground to rehearse these dynamics – that of collaborative and co-led, co-authored futures.

To find out more about Freedom Dreams email infofreedomdreams@gmail.com

Citations

- Sweetwater Foundation. (2021) ‘We the Publics…from Bounded Rationality to Unbounded Possibilities.’

- Morton, Timothy. (2013) ‘Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World’

BIOGRAPHIES

Paulina Reyes | RA, LEED Green Associate

Paulina Reyes is a registered architect and educator based out of Detroit. Paulina possesses a dedicated background in design-based research, community outreach, and the development of pedagogical efforts connecting cultural programming with the tools of architecture and urbanism. She acted as Project Designer-Manager for Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman, leading architectural and urban projects across the US-Mexico border, including fieldwork, and cross-border internship programming.

Sam Scardefield

Sam is a graduate of the University of Michigan M. Arch program, who deepened his work in “Regenerative Neighborhood Development after graduation with the Sweet Water Foundation in Chicago, IL. Sam is supporting Freedom Dreams as the Building//Projects Committee Lead, directing and implementing built projects within the Freedom Dreams Neighborhood. Sam is also the Manager of the MakerSpace Carpentry Apprenticeship where high school youth can develop trade skills, critical thinking, and design thinking through the fabrication of public infrastructure. He is also the founder of Open Works, LLC an emerging Design//Build practice that incorporates Community-Scale Production and Place-Based Education.