When I first moved to Detroit in 2014, my orientation to navigate to work, the grocery store, the theater, indeed anywhere I wanted to go, was centered around the freeway system. I raced along the Lodge, I-75, or I-94 not thinking about what might be happening in the neighborhoods reached by the off ramps that I flew past. When I wanted to see the water, I would drive to Belle Isle or down to the Detroit River, little realizing that the water once ran along Baby Creek, only a couple of blocks from my house in the Dexter Linwood neighborhood.

Then in Spring 2021, I joined a water walk around Belle Isle, organized by Hadassah Greensky, and began to learn about the physical and spiritual importance of water to Anishnaabe people and their way of life. Water is not only for drinking and irrigating land to grow food, but it is also a primary means of navigation and movement from one place to another. Indigenous names for the place we now call Detroit honor the area’s abundance of water; in Wendat, Karontaen, means “coast of the straits,” and Iroquoian, Teuchash Grondie translates in English as “the place of many beavers.” Beavers love creeks! For a place to have had many beavers it must have had many creeks for them to build their dams, find food, and raise their families.

As a new Detroit resident, I felt the need to reconsider my ways of orienting and navigating the city to — as Yuchi scholar, Dan Wildcat asks — “seriously reexamine and adopt those particular and unique cultures that emerged from the place I choose to live today,” and acknowledge “that the old ways of living contain useful knowledge for our lives here and now.”

The Mapping Detroit’s Buried Waterways project is my response to Wildcat’s request. It is a way to honor the old ways of orienting, building relationship with, and moving through the land known as Detroit, and a practical guide to navigating the city’s current streets through learning about and mapping the courses that the creeks followed, and in many cases still flow underneath the concrete.

This article is part of a three-part series, it explores the maps I used to find the creeks. Part II will look at my practice of mapping the creeks, and Part III will investigate the relationship between the creeks, the greenways projects across the city, and gentrification.

“The old ways of living.”

To start to learn about the old ways that water lived in Detroit, I began researching historical maps preserved in library archives. While these resources all center settler-colonial perspectives and place names, by approaching them with a different mindset I hoped to engage with a different version of history than the one presented on the maps’ surfaces. I wanted to engage with the creeks’ intrinsic value as living beings that facilitate connections between land, people, plants, and animals.

Probably the most famous creek in Detroit is Parent Creek, also known as Bloody Run. The creek still sees daylight near the place where Obwandiyag’s (Pontiac’s) land defenders were attacked by and defeated 250 British soldiers in July 1763.

One of the earliest known maps of Detroit, Carte de la Riviere du Detroit, drawn in 1752 by M. de Lery clearly shows Parent Creek, marked as R. Parent, already being encroached on both sides by French colonial settlers’ ribbon farms. Later US maps provide more detail on the route of Parent Creek in relationship to Detroit’s current streets and document the erasure of the creek as the city expanded.

Excerpt from Carte de la Riviere du Detroit showing French ribbon farms crowding around Parent Creek. Source: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Excerpt from Carte de la Riviere du Detroit showing French ribbon farms crowding around Parent Creek. Source: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

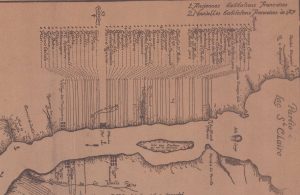

Section of Map of Wayne Co., Michigan showing Parent Creek, labeled Bloody Run. Source: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Section of Map of Wayne Co., Michigan showing Parent Creek, labeled Bloody Run. Source: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

In this section from Geil, Harley, and Siverd’s 1860 map of Wayne County the north fork of the creek, now labeled Bloody Run, has already been erased by the ribbon farms and the plots that will eventually bury the east and west forks are already planned.

By 1878, the entire creek north of Elmwood Cemetery had been disappeared under the area that now comprises the Eastern Market and McDougal Hunt neighborhoods. Today only a short section is visible in the Cemetery.

Photo of Parent Creek by Christiana

Further east from Parent Creek runs the creek that the French called the Riviere du Grand Marais (the river of the great marsh). The land around the river was appropriated by Joseph and Louis Trombley, and the river came to be known as Trombley’s Creek.

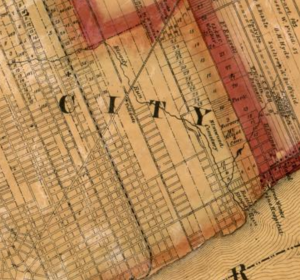

Section of Plan of the settlements of Detroit 1796: Reproduced in collotype facsimile from the original manuscript in the Clements Library, with a note by F. Clever Bold showing the creek and Louis Trombly’s ribbon farm. Source: Wayne State University.

Although descendants of the Trombley family continued to “own” land around the creek after Michigan’s ratification as a state in 1837, the creek was renamed Connor Creek for Henry Connor, who had been assigned ownership of land on the creek’s northeast side. Both Trombley’s and Connor’s land claims are shown on John Farmer’s 1855 Map of Wayne County, Michigan.

Clip from Map of Wayne County, Michigan: exhibiting the names of the original purchasers showing the land appropriated by Joseph Lewis Trembles (Trombley) and Henry Connor. Source: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Continuing east towards Lake St. Clair, Fox Creek is a shadow of its former self. Once running parallel to Lake St. Clair all the way from its connection with the Detroit River to the Milk River estuary, the creek now only sees daylight for a couple of short blocks in the Jefferson Chalmers community. For most of its northeasterly course, it is now trapped in a major sewer. Building along Connor and Fox Creeks and on the marshes where beavers once thrived and where the creeks connect to the Detroit River is one of main contributors to flooding in the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood.

Detail from Detroit Metropolitan Area Planning Commission 1962 Major Areas in need of Sanitary Sewer Services. The sewer that encloses Fox Creek along its original course is highlighted in blue. Source: Wayne State University.

Detail from Detroit Metropolitan Area Planning Commission 1962 Major Areas in need of Sanitary Sewer Services. The sewer that encloses Fox Creek along its original course is highlighted in blue. Source: Wayne State University.

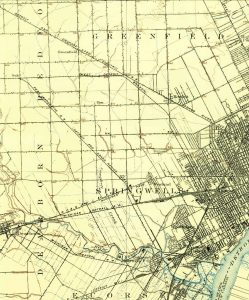

On Detroit’s Westside, US settlers were also naming creeks for themselves. James Baby and George Campbell appended their names to Baby Creek and Campbell Creek, respectively. Both creeks join the Detroit River in the Springwells area. Baby Creek is now buried under the Claytown and Petoskey-Otsego neighborhoods, and various branches of Campbell Creek are encased in the concrete of Barton-McFarland, Bethune, and Rosedale Park communities among others. The creeks are still clearly visible as late as 1905 on the US Geographic Survey maps of Detroit, which also shows the many ditches and canals built by ribbon farmers and later settlers to irrigate their land with water from the creeks’ main channels.

Clip from 1905 USGS 1:62,000 Series showing Baby and Campbell creeks and their many natural tributaries and man-made canals and ditches. Source: United States Geological Survey

The courses of Parent, Connor, Fox, Campbell, and Baby Creeks were all relatively easy to find. They were included on maps well into the late 1800s and early 1900s, many of these maps have been digitized and are accessible online. Much more difficult to locate are Mays Creek and Savoyard Creek which once flowed through what is now downtown Detroit.

There has recently been a resurgence of interest in Mays Creek with the opening of the Southwest Greenway, which runs over a section of the creek. Settler after settler slapped their name on the creek as the land “ownership” around it changed hands. It was first recorded as Campeau’s Mill Creek, then Cabacier’s Creek, May’s Creek, and finally Peltier’s Creek. In 1848 the railroad built along the course of the creek and within a few years May’s Creek was buried and built over.

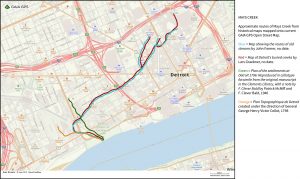

Mays Creek routes

In the heart of what is now downtown Detroit, Savoyard Creek was the first creek to be drawn on colonial maps. It is marked on many old maps of Fort Detroit as Ruisseau de Rurtus or River Xavier. It was also the first creek to be converted into a sewer and buried beneath the city. Savoyard Creek has not seen the sun since 1836, and it still runs through its brick lined coffin.

Detroit in 1796 from Western Literary Cabinet. Source: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

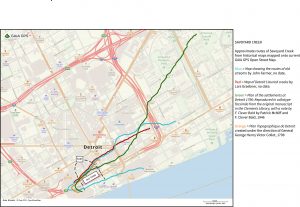

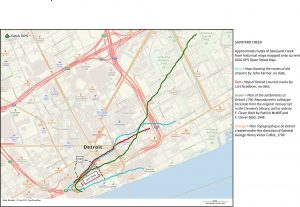

Savoyard Creek routes

“Useful knowledge for our lives here and now.”

Visiting libraries, exploring the maps, and seeing the courses and names of the creeks change over time is fascinating. I could have sat in my living room tracing the creek routes onto a current map of Detroit, which would probably have taken a couple of days and oriented me to nothing more than the relationship between my couch and my fridge. That approach seems very out of keeping with Dan Wildcat’s definition of decolonization and it certainly would not facilitate connections with the creeks or honor their value as living beings. Instead, using GIS technology I have set out to map the creeks by walking and biking all of Detroit’s buried waterways, the creeks, the canals, the drainage ditches, and the rivers. I have been at it for more than a year now and am still far from completing the project.

Part II of this series of articles will explore my process and the different mapping practices I am using in the project.