There are borders all around us. From our declarations of membership in a particular nation, to our identifications with our particular states, cities, or neighborhoods, to our establishment of cliques or crews where acceptance is limited to those with whom we feel we share some bond, to our claims of ownership over certain territories or lands, we are constantly surrounded by the language of exclusion and inclusion based upon often arbitrary lines drawn on maps long ago. We are so used to this language that we often make these declarations as if they are fundamental to letting others know key aspects about ourselves, to ensuring that they are aware of our right to be in a certain place at a certain time, to guaranteeing our opinions will be taken as Truth about how we experience our place in those spaces, to signaling our right to a sense of belonging, to justifying our denying entrance to those we deem outsiders, to shutting out voices that may complicate our perceptions of community.

Borders elicit both danger and security. Borders serve both to shield us from interlopers, gentrifiers, colonizers, and ne’er-do-wells, while at the same time enacting a protracted colonial mission to carve up the world for its resources, keep people at one another’s throats as we battle over the fallacy of scarce resources, and allow for a worldview which sows mistrust rather than love. Borders are indeed thorny to navigate.

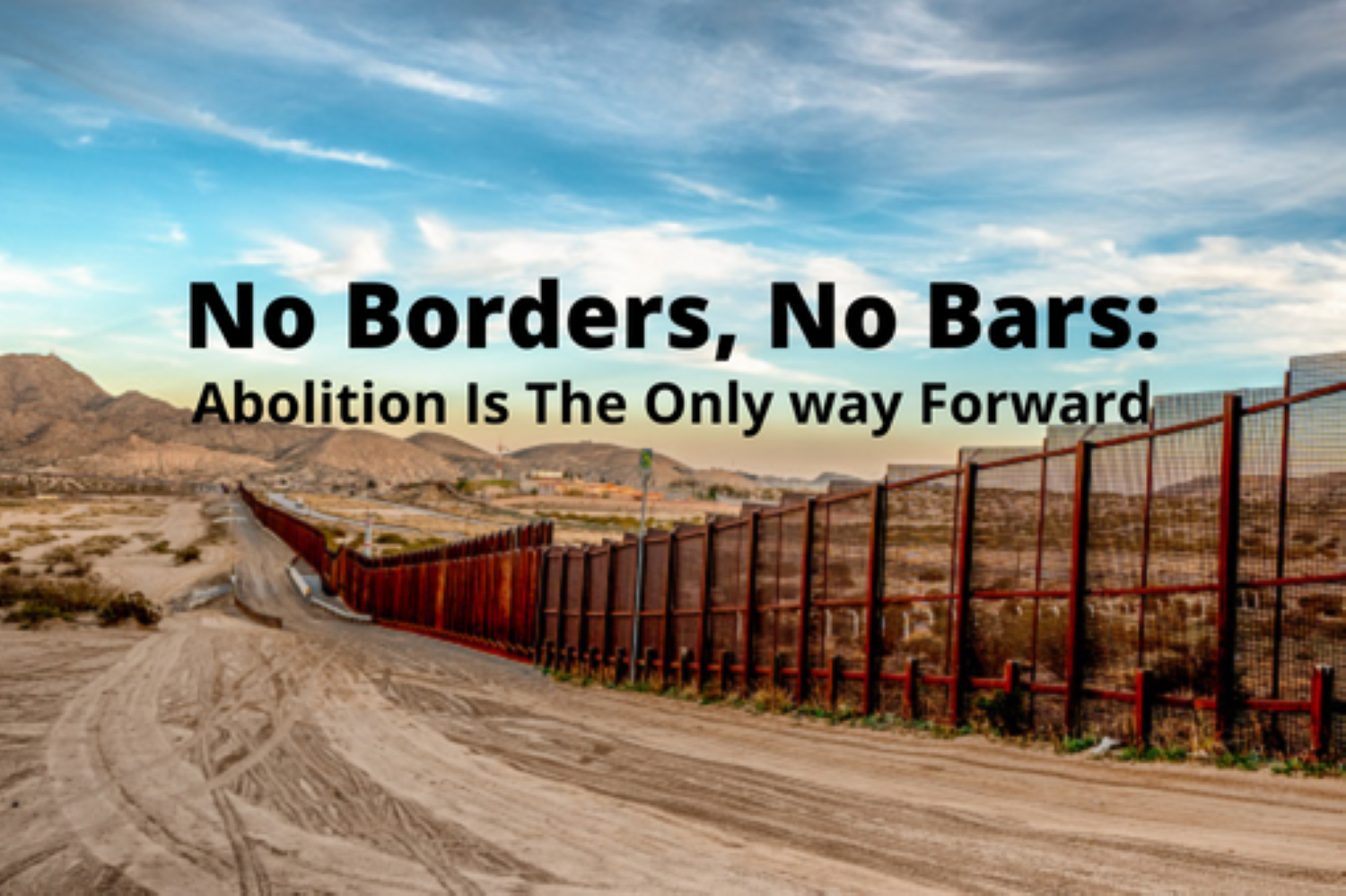

It is from this place of seeing the ways in which borders can provide us with a sense of grounding and connectedness to others around us and give credence to one’s right to merely exist within this violent structure, while at the same time ripping our shared humanity apart in soul-wrenching ways, that we here at Riverwise have been thinking about this current issue. As we grapple with ideologies of abolition, it is exceedingly important that we recognize the inter-connectedness of a language built upon a violent understanding of borders, with narratives that deem certain bodies (most generally Poor, Black or Brown) in need of indefinite detention, others (largely women) in need of state sanctioned incursions to control even inside our bodies, and most poignantly that deny shared humanity, dignity, bodily autonomy and respect to anyone who falls outside of a narrowly defined white patriarchal power structure.

It is not only time to decolonize the actual physical spaces of this earth, it is time to decolonize our minds. And that is going to require that we let go of the false and detrimental notion of “the American Dream.” Indeed, this nightmare has time and again pitted us against our most likely allies (people of the Diaspora, immigrants, the Poor, the formerly incarcerated, struggling families, the un-homed) as we cling to the idea that they are standing in our way, stealing our opportunities, and that if we can just MAKE IT in the West, somehow all of the suffering it has produced domestically and internationally will have been worth it, may actually lead to some kind of justice, may eventually produce peace. Make no mistake, it won’t. It never will. No amount of wealth, no amassing of material goods, no filled quotas of Black, Brown, or Women CEOs is ever going to make this system good, atone for its sins, make it okay. The dispossession, murder, mass incarceration, impoverishment, decimation and denigration of our natural world and fellow species, is a feature of this system, not a bug.

One thing that is clear from the outpouring of submissions we received when we put out the call for this edition’s theme of “NoBorders, No Bars,” many of you couldn’t agree more. Through his cover art, Detroit based artist Wayne Curtis, makes a bold statement about the webs that link the monied interests of the 1% with slavery, mass incarceration, and the constant struggle to rise up against a system which is geared towards the commodification and erasure of Black, Brown and poor people. Through his back cover collage, Will Langford centers this rebellion and its champions throughout history who have long used art, music, poetry, and self-expression as a {r]evolutionary tool to remind us that other worlds are possible.

In their deep reading of Border & Rule by Harsha Walia, and the attendant study guide produced by their community circle , PG Watkins, Alexis Shotwell, & Mike Doan, provide us with an example of mental decolonization. They show us that focused and serious political education, carried out in community, with the visionary understanding that we must do the work, and be willing to interact with new theoretical frameworks, even if that feels uncomfortable at times, is essential. In this same vein, Charles Ferrell’s fiery analysis of the teachings of Guyanese revolutionary Walter Rodney, synthesizes the history and underpinnings of a need to expose the Truth behind Western imperialist and white supremacist ideologies, with present barriers to liberation. He challenges all of us to question the narratives, ideologues, and pundits who claim to be working on our side. And in his piece on Palestinian liberation and the death of Shireen Abu Akleh, Hani. A, exposes as well that our reliance upon borders as a marker of belonging often folds in upon itself as we are pressed time and again to keep adding requirements for inclusion that ultimately end up excluding those most vulnerable, those most in need of our camaraderie.

Poetic offerings from Catalina Rios, Iye Inaeade, Byron Tebeau, and some of our Riverwise workshop poets, provide us with beautiful and haunting testimonies about the realities of traversing a world designed around violence, and designed to keep us locked in repeated cycles of trauma. Their words both sear us into an awakening, while providing the salve of healing awareness. Much in the same way, Adrienne Ayers discussion of her work as a reiki practitioner as an explicitly revolutionary act, is compelling, as it reminds us that in a system hell-bent on damaging us, sometimes the most rebellious thing we can do is take time to heal, extend some of our strength to those in our communities who are suffering, and never forget that our safety actually lies within one another, not ever within this capitalist, fascist, neo-liberal, militarized, racist, misogynistic, prison state.

As you read this edition, hold the intention of questioning and reflecting upon the notion of boundaries. Which ones do we actually need? Which ones do not serve our purpose? Indeed, as the Supreme Court of the United States has just handed down a ruling that tells more than half of the US population that they are not guaranteed the right to control the boundaries of their own bodies, it is clear that some borders are good. Your beliefs should end where my skin begins. Further, as discussed by Natalie Gallagher, with the Supreme Court’s other recent ruling in Egbert v. Boule which expands Border Enforcement Zones, we can interpret borders in another way in which the paradoxically both ever-tightening and widening of border ideology threatens everyone’s right to peace. Do not be lulled by the false sense of security that the term “citizenship” may bring. In a system such as this, be forewarned that the goal is never actually your freedom, self-actualization, or safety.

Thus, in this issue we also highlight the deep well of strength, support, and humanity that is cultivated by the many wonderful humans across the city, who have long worked in solidarity with both people and ideologies that traverse global boundaries. Drawing from Pan-Africanist, socialist, communist, revolutionary, anti-capitalist, anarchist, rebellious, loving, and humane traditions, Rukiya Colvin and Rich Feldman provide us with an active view of building “beloving” community through the work of numerous groups to cultivate leadership, provide education, produce counter-narratives, develop networks of real security based upon food and tech sovereignty. These examples show us that another world isn’t just possible, it’s actively at work.

As we move forward on our journey toward dismantling all of the walls we have built around our bodies, our minds, our spirits, we must work hard to also dismantle the narratives we cling to that provide us the illusion of absolution from accountability. Just as we scoff when we hear someone say “but I’m poor/I’m not racist…so I’m not at fault for Black and Brown suffering in this country” we too must begin to scoff when we who are Black and Brown use those same justifications to deny rights to those whose claims may come from other shores, whose ideologies may sound strange, but whose claims are just as real as our own. There is no oppression Olympics, just oppression, and the need for it to come to an end. Decolonizing our minds thus means opening them to the possibility that our minds are indeed colonized, to accepting that everyone is susceptible to the intoxication of hate, and that the real enemy is any line of thought which judges a person or the earth or any other species value by what it can earn in the free market.

True abolition will require more love than most of us think we have, but we must trust that we do. It will require bold experimentation, patience, persistence, and a radical commitment to seeing liberation not as a buzzword, but a way of life. It will require seeing any other human who is suffering as someone to whom we extend a hand, rather than turn our shoulder out of fear of or dislike for the unknown. It will require detaching our identity from any one place, any one time, so that we see the human first. It will require moving beyond the notion that in order to have your human rights acknowledged you must have “official” papers stamped in triplicate. It will take seeing justice not as locking people away to rot but figuring out how we actually move beyond trauma in ways that evoke growth. It will involve debates and compromise, so long as the compromise is never at the expense of anyone’s humanity. It will require moving beyond the worship of royalty, celebrity, idolatry, until we see in each human being something so special that we are horrified we ever thought they weren’t worthy of belonging, of surviving, of thriving. It will require all of us.

Whose side are you on my people? Whose side are you on?